Metalinguistic Approach to Biliteracy Instruction

Metalinguistic Approach to Biliteracy Instruction

Jill Kerper Mora

This module describes the theories of metalinguistics and how these theories apply to biliteracy learning and instruction.

The Metalinguistic Model

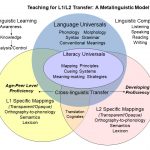

Dr. Mora presents a metalinguistic model of teaching for transfer depicts the overlap and distinctions necessary for understanding cross-linguistic transfer of reading skills. This model is based on an explicit theory about the relationship between spoken and written language forms and the research evidence of cross-linguistic transfer in biliteracy learning (Odlin, 1989). Language is a set of arbitrary symbols, conveyed primarily by units of sound and systematic patterns of words and sentences that have conventional meanings within a speech community. Language universals are the characteristics and subsystems that are common to all languages. Therefore, a speaker of any language employs these features of language for communicative purposes. The processes of reading and concepts about the relationship between speech and print that apply to all languages are called literacy universals. Both language and literacy universals are learned and applied as biliteracy develops. There are three prerequisite skills required for the development of competencies in literacy: 1) Competence with the oral language; 2) Understanding of symbolic concepts of print; and 3) Establishment of metalinguistic awareness:

It is important to keep in mind what we are teaching when we teach the alphabet and phonics to beginning readers. Reading and writing are based on metalinguistic knowledge of how language is represented symbolically through a graphic system. Students learn the alphabetic principle, or how oral language is “mapped” unto print, when they learn to read. That is, they learn that there are consistent letter-sound (grapheme-phoneme) correspondences and spelling patterns that they can decode into comprehensible language. We assume that students are developmentally ready to learn the alphabetic principle of their native language, which they speak proficiently at a level equivalent to their age peers. We proceed with literacy instruction based on students’ linguistic, cognitive and motivational readiness. Students must have sufficient linguistic development to be able to communicate their own messages and receive messages from adults and each other. They must also be interested in doing so, in order to be able to focus on how to communicate through writing and reading. Written text is a symbolic system for recording spoken language. Therefore, reading is essentially a metalinguistic skill since it requires attention to and analysis of how language is constructed from combinations of its parts that are recombined in patterned and predictable ways to convey meaning. We must think of reading as a “recoding” process rather than simply a decoding process, since readers must recode written language into understandable language. Consequently, learning to read requires understanding the meaning of symbolic representation as an abstract concept. Written symbols do not carry meaning on their own, but can only be understood as words, sentences and discourse that duplicate or parallel communicative acts performed through a linguistic system.

Metalinguistic Awareness (MA)

Metalinguistic awareness is a term used to describe a construct, theory or model to explain the interaction between language and written text, primarily in bilingual learners’ literacy development (Bialystok, 2007.) Metalinguistic awareness (MA) is defined as awareness or a bringing into explicit consciousness of linguistic form and structure in order to consider how they relate to and produce the underlying meaning of utterances. MA is also termed metalinguistic ability. The construct describes the ability to make language forms objective and explicit and to attend to them in and for themselves. MA is the ability to view and analyze language as a “thing,” language as a “process,” and language as a “system.” MA in bilingual learners is the ability to objectively function outside one language system and to objectify languages’ rules, structures and functions. Code-switching and translation are examples of bilingual individuals’ metalinguistic abilities.

Metalinguistic abilities develop over time in dual language learners along with increasing language proficiency and their understanding of languages as symbolic representational systems. Metalinguistic awareness leads to metalinguistic knowledge (MK) through a continual and simultaneous process of developing linguistic control and cognitive abilities. Metalinguistic learning proceeds from implicit understanding and unarticulated knowledge through non-structured experiences toward explicit understanding and articulated knowledge through structured experiences such as direct instruction in transference knowledge and skills: 1) Students’ implicit unarticulated knowledge of language form and function can be made explicit through structured learning experiences and purposeful uses of text. This metalinguistic awareness leads to explicit knowledge about how languages work and the ability to articulate this knowledge. This metalinguistic knowledge results in increased self-regulatory control over language production and increased use of language in cognitive performance. These processes support transfer of learning through what general transfer of learning theory defines as “mindfulness” and “cognitive habit” formation which is carried across language-learning settings in response to pragmatic and functional demands of the interactions and academic tasks.

Language Universals

Teachers in dual language programs and of English Language Learners in monolingual English classrooms benefit from viewing language acquisition and literacy instruction and learning from the perspective of language universals, literacy universals, language-specific knowledge and cross-linguistic transfer. Teachers’ effectiveness is enhanced when they plan and implement L2 and literacy instruction with an overarching understanding of what awareness, knowledge and skills beginning readers and writers need to know about language universals and language-specific forms and features of Spanish and English or students’ other-than-English native language. Metalinguistic learning requires attention to language components and forms, growing from an implicit and practical knowledge based on students’ oral language abilities to awareness, and then conscious and deliberate analysis and control of linguistic features in speaking, reading and writing. In their study of dual immersion programs in Canada, Wallace Lambert and Richard Tucker (1972) observed that students became “incipient contrastive linguists” as they compared and contrasted their two languages and became “linguistic detectives” inquiring into cross-linguistic relationships such as cognates and language structures.

Knowledge of How Language Works

The science of linguistics tells us that language is a rule-governed system made up of components or subsystems that work together in consistent and predictable ways to produce meaning. Languages have meaning based on arbitrary conventions that agree on a symbolic representation for words and patterns or sequences of words that are associated with concepts and ideas. Language is rule-governed and integrative across the language subsystems of phonology, morphology, grammar & syntax, and semantics. These subsystems or components contain language universals that are common to all languages and also contrasting features that are particular to a certain language. In literacy, biliteracy teachers also attend to the orthographic system, which involves the study of how spoken language is mapped unto written symbols. In addition, biliteracy teachers are knowledgeable about the various functions and uses of language and how these prompt variations in levels or formality, expressions and other features of language according to the communicative goals and tasks that learners perform. Here we examine the theoretical origins of our current thinking in biliteracy education about the importance of students’ learning about language.

Contrastive Linguistics

The academic discipline of contrastive linguistics studies the similarities and differences between languages to arrive at a scale of language distance between two linguistic systems. There are mental constructs or abstractions that DL learners acquire as their metalinguistic awareness and knowledge grow across the grade levels. Students evolve an awareness and knowledge that language is rule-governed. For example, Spanish speakers become aware in the course of making sense of ordinary language that nouns have number and gender and the articles and adjectives that are used to modify them must agree according to certain fixed rules. They learn to use agreement correctly in their speech. However, as they begin to develop metalinguistic knowledge, this concept is articulated as a grammatical rule or generalization and this understanding of this linguistic construct is reinforced throughout the grades.

Table 2. Components of Metalinguistic Knowledge by Language Subsystems

| Component of Metalinguistic Knowledge | Universal Application | Teaching Constructs: English | Teaching Constructs: Spanish |

| Phonological Awareness | Words are composed of phonetic units. We can analyze words to segment their component parts. This helps us figure out how to “map” language sounds from and into print. | Word meaning often depends on a “one-phoneme” difference, such as in minimal pair words. The position of the phoneme in the word is important in determining meaning.

Ex:bear, fair, pair, spare and in pat, pit, pot, put Special attention is given to English phonemes that don’t exist in Spanish |

In addition to phonemic distinctions that determine word meaning, accentuation or syllable stress/emphasis is important. Readers must attend to the way word syllables are pronounced in order to discern differences in meaning. This aspect of PA is related to orthographic knowledge about the use of the written accent mark. Ex: Ability to hear the difference between presente and presenté |

| Morphological Awareness | A morpheme is the smallest unit of meaning. Morphemes can be combined in words to change or expand their meaning. Some spelling is morphological rather than phonological. | The past tense inflection is most frequently spelled by adding –ed to the verb, regardless of how it is pronounced. Ex: pushed, shoved, shouted all end in –ed but the morpheme is pronounced differently in each case. | Ending can be added to words to change their meaning, such as to make express little, few or less or bigger and/or more. Ex. casa, casita, casona; un ruidito, un ruidón; grandísimo, grandotote, grandecito. |

| Lexical/Semantic Awareness | There is the construct “word” that describes the boundaries of a linguistic unit that expresses an abstract conceptual referent. Knowledge of categories or classification schemas for words helps us understand “word families” that convey related meanings. | Some words sound the same but have different spellings according to their meaning in context.

Ex:there, their, they’re; two, to, too |

Some words are spelled the same but have different meanings. The accent mark is used to distinguish these words from one another.

Ex: Si, sí; mi, mí; tu, tú |

| Syntactic Awareness | Word order often signals meaning. There are groups of words in a certain order that have a particular meaning that separately they do not have (idiomatic expressions, phrasal verbs, etc.) | Teaching idiomatic expressions as a unit of meaning. Ex:

The difference in meaning between “The man ran out of the burning building…” as compared to “The man ran out of gas on the freeway…” |

Two-word and three-word phrases have different meanings depending on the word order. Ex: un hombre pobre, un pobre hombre; el antiguo presidente, el presidente antiguo; una señora grande, una gran señora (gran is an apócope of grande); “Más vale un vieja mula que una mula vieja:” |

| Grammatical Awareness | Language is rule governed. Certain forms of words convey meaning regarding number, gender, tense and mood. | In English, the possessive pronoun is singular or plural depending on the number of possessors, not the number of objects possessed. Ex: her coat, his coats, their coat, their coats. | In Spanish, the possessive pronoun form indicates both possessor and the number of objects possessed. The forms su/sus can indicate either singular or plural numbers of possessors (third person). Ex. mi libro, mis libros, su libro, sus libros (de él, ella, usted, ustedes, ellos) |

Instruction for Metalinguistic Knowledge Development

- Teachers build on students established & developing knowledge of their Home Language (HL) in teaching their new Language (NL).

- Instruction focuses on how language works to convey meaning through the subsystems of language.

- Teachers develop metalinguistic concepts, principles and analysis, not just phonics or grammar rules.

- The curriculum progresses from language universals that apply generally to all languages into specific features of students’ heritage language and English.

- Teachers facilitate transfer through direct instruction, embedded teaching and “teachable moments.”

Click here for a description of the components of metalinguistic knowledge in Spanish and English.

Click here for a Metalinguistic Knowledge Development Continuum

Source

Mora, J.K. (2025). Spanish language pedagogy for biliteracy programs. San Diego, CA: Montezuma Publishing