A Multilingual Educator Fact-Checks SoR Claims

Fact-checking Ten Science of Reading Claims: A Multilingual Educator’s Perspective

Jill Kerper Mora, Ed.D.

San Diego State University

The format for this fact-checking of the Science of Reading (SoR) from the perspective of multilingual learner education and the description of the SoR claims are based on the book by Robert Tierney and P. David Pearson titled Fact-checking the Science of Reading: Opening up the Conversation. The Fact-Checking (2024) book is available for free access from Literacy Research Commons.

Click here to view A Multilingual Educator Fact-checks SoR Claims: Executive Summary

- SoR Claim 1 Explicit systematic phonics instruction is the key curricular component in teaching beginning reading.

- SoR Claim 2 The Simple View of Reading provides an adequate theoretical account of skilled reading and its development over time.

- SoR Claim 3 Reading is the ability to identify and understand words that are part of one’s oral language repertoire.

- SoR Claim 4 Phonics facilitates the increasingly automatic identification of unfamiliar words.

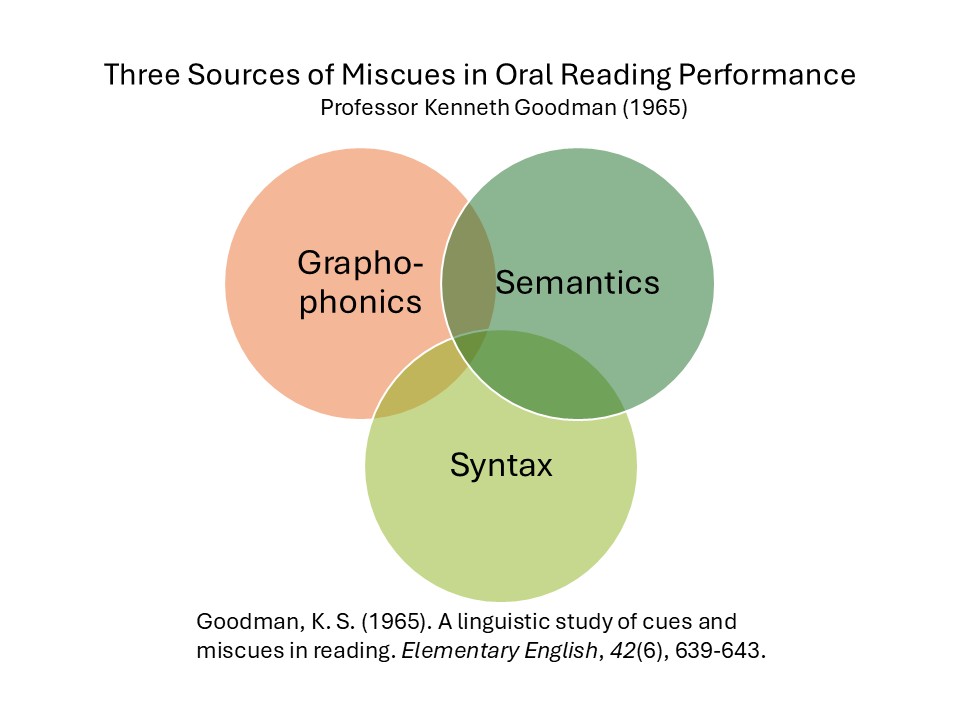

- SoR Claim 5 The Three-Cueing System (Orthography, Semantics, and Syntax) has been soundly discredited.

- SoR Claim 6 Learning to read is an unnatural act.

- SoR Claim 7 Balanced Literacy and/or Whole Language is responsible for the low or failing NAEP scores we have witnessed in the U.S. in the past decade.

- SoR Claim 8 Evidence from neuroscience research substantiates the efficacy of phonics-first instruction.

- SoR Claim 9 Sociocultural dimensions of reading and literacy are not crucial to explain either reading expertise of its development.

- SoR Claim 10 Teacher education programs are not preparing teachers in the Science of Reading.

- REFERENCES Topic Bibliographies

SoR CLAIM 1

Explicit systematic phonics instruction is the key curricular component in teaching beginning reading.

Tierney, R. J., & Pearson, P. D. (2024). Fact-checking the Science of Reading: Opening up the conversation. Literacy Research Commons.

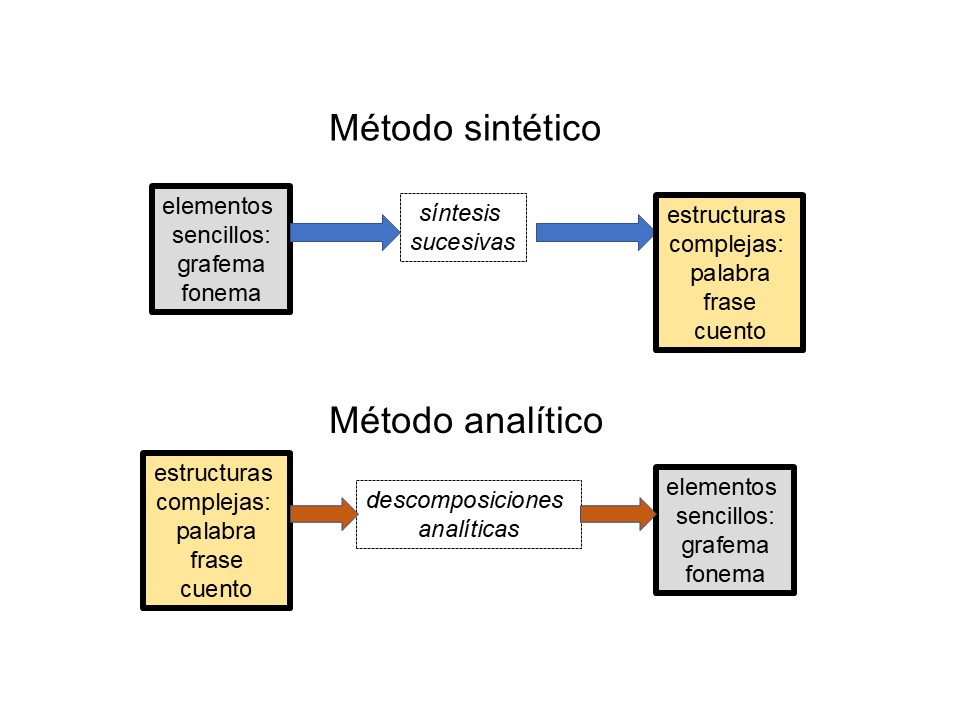

Bilingual educators teach phonics in two languages. Spanish phonics is much easier to learn than English phonics because Spanish has a transparent orthography. On average, it takes one to three years for a Spanish speaker to learn to read Spanish (Alegría & Carillo, 2014: Jiménez & Ortiz, 2000). Contrarily, it takes from three to five years for an English speaker to learn to read English (Seidenberg, 2013; Share, 2004).

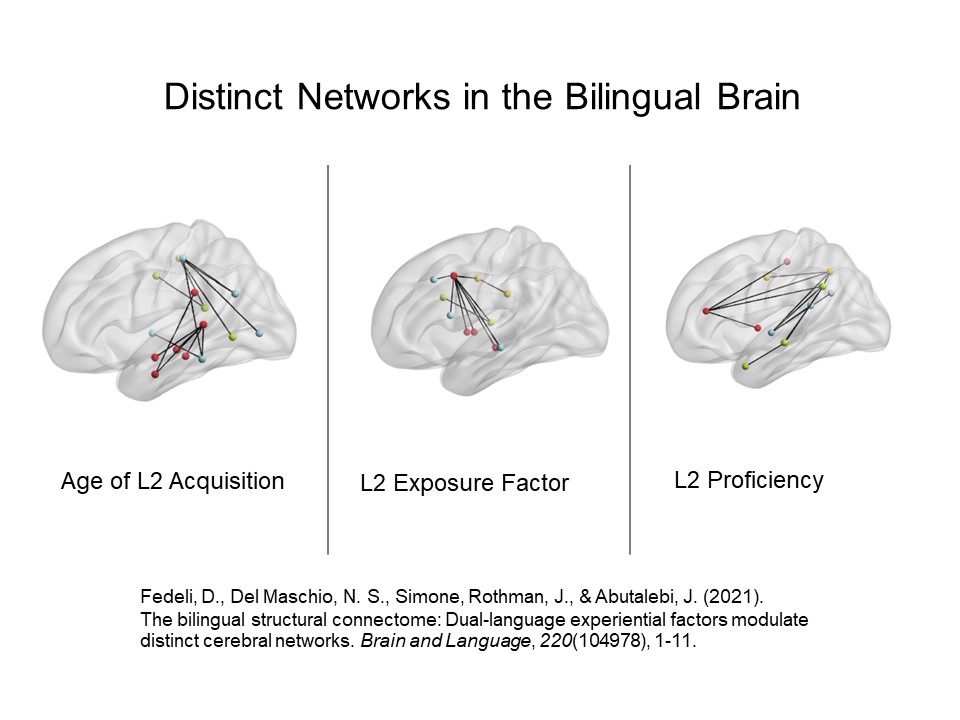

The question of how and how much explicit and systematic phonics instruction needs to be implemented is not a question that research can answer. This determination depends on the linguistic and cultural characteristics of the students receiving the instruction. For example, Spanish/English bilingual learners who are biliterate and have learned to read in Spanish need much less explicit instruction in English phonics when learning to read in English as a second/additional language (Fedeli, et al., 2021: Petito, et al., 2012). This is because many letter-sound correspondences are directly transferable across languages (Mora, 2016; Mora & Dorta-Duque de Reyes, in press; Thonis, 1983). Students who are literate in their native Spanish have mastered alphabetic decoding. Their phonological/phonemic awareness is well developed and transfers across languages. There is no fixed sequence for English phonics instruction needed for these students because, as fluent readers of Spanish, they already have a full repertoire of phonetic decoding skills (Jiménez, García & Pearson, 1996; Kovelman, et al., 2015; Marks, et al., 2022).

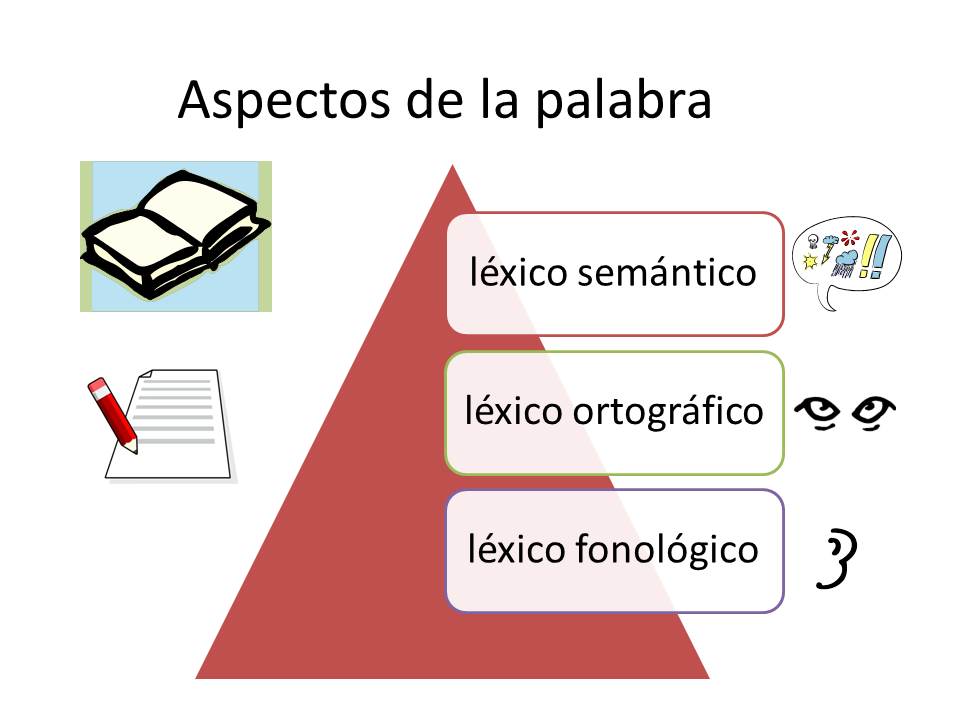

Orthography is the study of how oral language is represented systematically in writing. The term comes from the Latin roots ortho meaning “straight” or “correct” and graph meaning writing, or how to write correctly (Apel, 2011; Smith, et al., 2021; Templeton, 2025). Orthography is more than spelling since it refers to all aspects of written language such as punctuation, word spacing and special features used to signal meaning. Orthographic systems have varying degrees of consistency and regularity in terms of the one to one or multiple relationships with phonetic and morphological units of the language and the use of single letters or letter clusters and combinations to represent different phonemes and morphemes. The writing system represents oral language sounds, the reader must recode the written forms into language, which requires metalinguistic knowledge of how the symbolic writing system operates. A writing system represents oral language sounds, the reader must recode the written forms into language, which requires metalinguistic knowledge of how the symbolic writing system represents speech (Ferreiro, 2009: Vernon, 2007). This is referred to as the alphabetic principle or “mapping” sounds onto print, where the reader makes speech to print connections to comprehend a text. The term in Spanish is alfabetización. In biliteracy instruction, teachers make explicit contrasts and comparisons between the two language systems that students are learning, which increase their awareness and knowledge of how the languages are represented in written text. This explicit knowledge formation supports development of problem-solving strategies in decoding and comprehending text (Anthony, et al., 2009; Cano Muñoz & Vernon, 2008; Escamilla, et al., 1996; Ferreiro & Tolchinsky, 1979; Flores, 2025; Gil, 2019; Padrón, 1992; Signorini & Borzone de Manrique, 2003; Tolchinsky, 1990; Vernon, 2007).

Orthography is the study of how oral language is represented systematically in writing. The term comes from the Latin roots ortho meaning “straight” or “correct” and graph meaning writing, or how to write correctly (Apel, 2011; Smith, et al., 2021; Templeton, 2025). Orthography is more than spelling since it refers to all aspects of written language such as punctuation, word spacing and special features used to signal meaning. Orthographic systems have varying degrees of consistency and regularity in terms of the one to one or multiple relationships with phonetic and morphological units of the language and the use of single letters or letter clusters and combinations to represent different phonemes and morphemes. The writing system represents oral language sounds, the reader must recode the written forms into language, which requires metalinguistic knowledge of how the symbolic writing system operates. A writing system represents oral language sounds, the reader must recode the written forms into language, which requires metalinguistic knowledge of how the symbolic writing system represents speech (Ferreiro, 2009: Vernon, 2007). This is referred to as the alphabetic principle or “mapping” sounds onto print, where the reader makes speech to print connections to comprehend a text. The term in Spanish is alfabetización. In biliteracy instruction, teachers make explicit contrasts and comparisons between the two language systems that students are learning, which increase their awareness and knowledge of how the languages are represented in written text. This explicit knowledge formation supports development of problem-solving strategies in decoding and comprehending text (Anthony, et al., 2009; Cano Muñoz & Vernon, 2008; Escamilla, et al., 1996; Ferreiro & Tolchinsky, 1979; Flores, 2025; Gil, 2019; Padrón, 1992; Signorini & Borzone de Manrique, 2003; Tolchinsky, 1990; Vernon, 2007).

It is worth noting that a study of Spanish literacy instruction that compares the ways in which phonological awareness is taught in schools in Mexico as compared to instruction in bilingual programs in the United State (Goldenberg, et al., 2014). These researchers describe their findings as follows, while also proposing an causal effects of a primary emphasis on written language and the transparency of Spanish orthography in contrast to the opaque orthography of English:

Phoneme-oriented instruction was seen in 85% of the U.S. K classrooms (in nearly 94% of English-instructed classrooms and 79% of Spanish instructed classrooms). In Grades 1 and 2, we saw phonemic instruction in 56% of U.S. classrooms but in fewer than 9% of Mexican classrooms. Aside from this contrast, the most noticeable difference between the Mexican and U.S. classrooms that we observed was the far greater percentage of time spent in activities and questions related to reading comprehension in Mexican classrooms compared to U.S. classrooms. In first grade, comprehension activities and questions were observed during 29% of the time in Mexico and between 7% and 8% of the time in the U.S. classrooms. The contrast in second grade was 24% of the time observed in the Mexican classrooms and between 13% and 15% of the time in the U.S. classrooms. (p. 617)

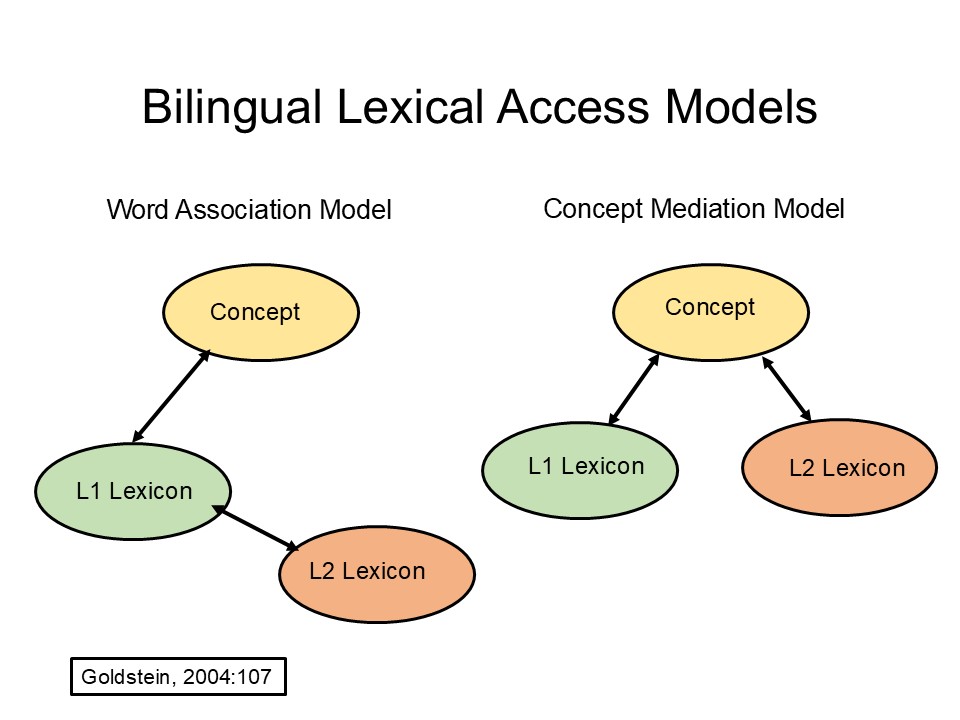

The features of effective phonics instruction for multilingual learners must include contextualization of word recognition skills in relationship to word meanings (semantics) to enhance vocabulary development. This requirement is supported by empirical research in second language reading on lexical inferencing (Haastrup, 2009; Nassaji, 2006; Raudszus, Segers & Verhoeven, 2021; Wesche & Paribakht, 2009). Explicit instruction is an issue of effectiveness for metalinguistic learning where the objective is to make explicit the knowledge of how language(s) work, knowledge that underlies multilingual learners’ first and second language competence (DeKeyser, 2003; Ellis, 2005; Francis, 2011). Isolated and decontextualized phonics instruction is counter-indicated for multilingual learners because vocabulary is retained in memory through word-context associations are made at the conceptual level rather than the word-form level (Francis et al., 2019). The use of decodable texts for Spanish literate students is not recommended because decodables are modified and artificial English language that decreases students’ ability to utilize natural English syntax and grammar for meaning making.

Spanish Phonics Instruction in Dual Language Programs

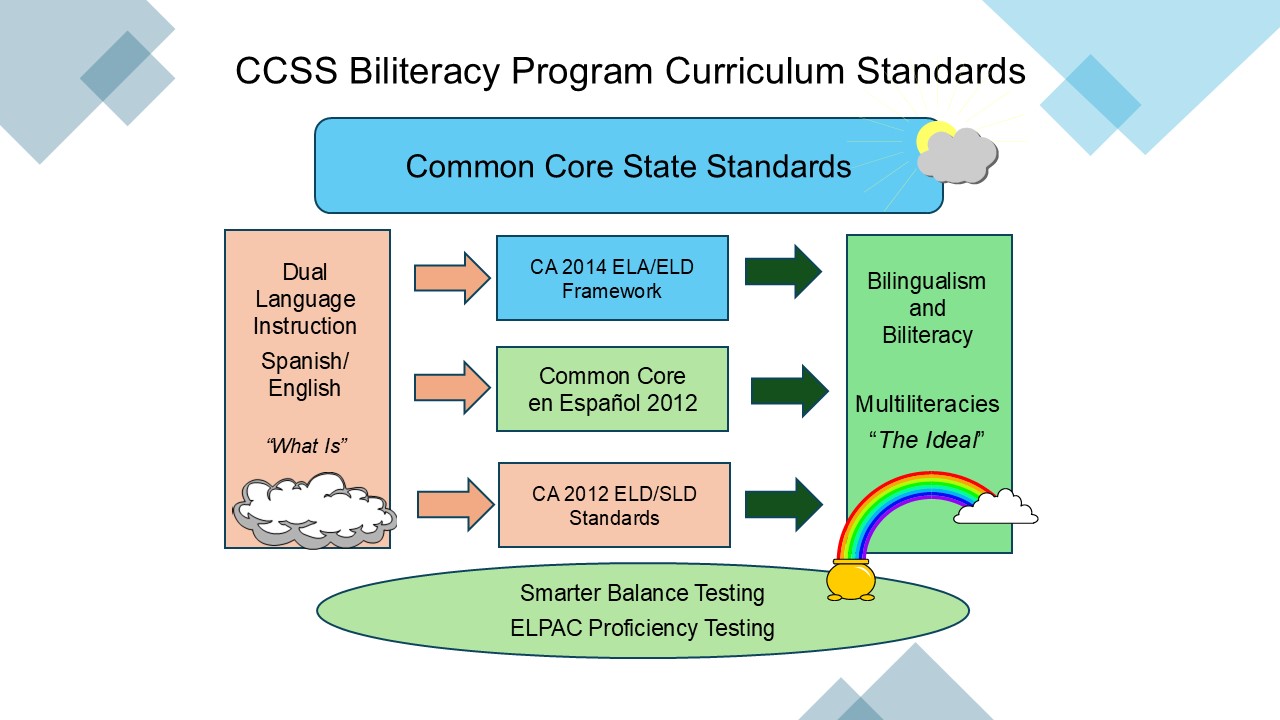

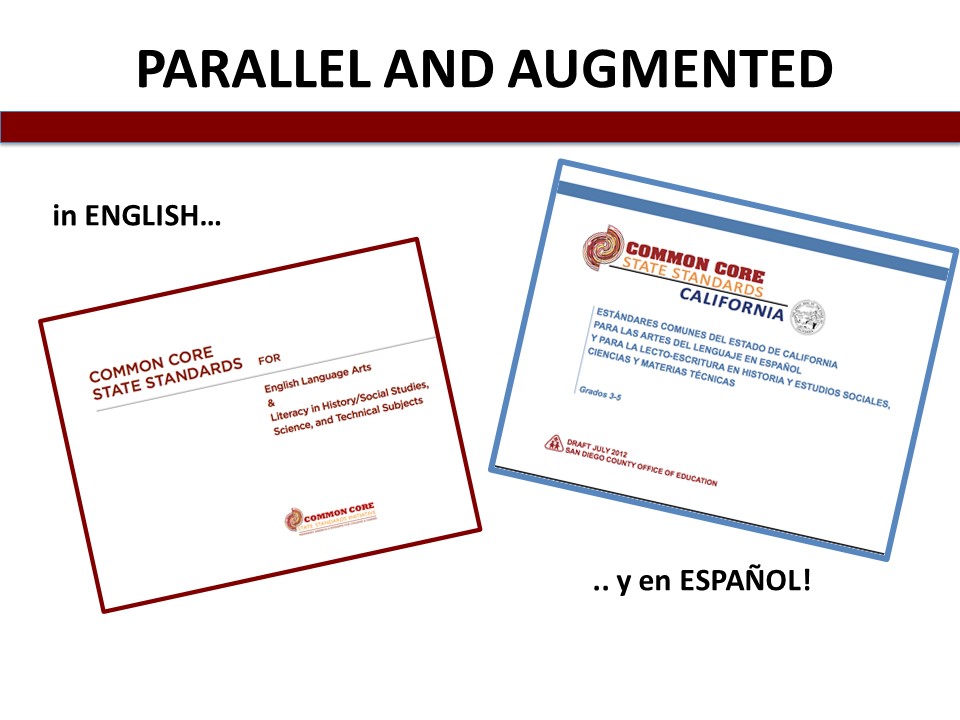

The San Diego Office of Education published the Common Core Standards Translation Project. The translation included a linguistic augmentation to specify Spanish-specific orthographical and grammatical knowledge needed for decoding and comprehending Spanish text. A project of the Council of Chief State School Officers, the California Department of Education, and the San Diego County Office of Education, the Common Core en Español Spanish translations and linguistically augmented versions of the CA CCSS to support equitable assessment and curriculum development.

The San Diego Office of Education published the Common Core Standards Translation Project. The translation included a linguistic augmentation to specify Spanish-specific orthographical and grammatical knowledge needed for decoding and comprehending Spanish text. A project of the Council of Chief State School Officers, the California Department of Education, and the San Diego County Office of Education, the Common Core en Español Spanish translations and linguistically augmented versions of the CA CCSS to support equitable assessment and curriculum development.

The parallels to metalinguistic concepts and skills between English Language Arts and Spanish Language Arts are articulated in this standards document. This curriculum document presents a sequence of metalinguistic knowledge concepts, known as the Common Core en Español Standards (2012). The standards’ scope and sequence reflect a progression of linguistic competence and demands of academic tasks. The grade-by-grade articulation of metalinguistic concepts categorized by language subsystems to illustrate how knowledge of how language works is applied to students’ performance of academic language and literacy tasks in English and Spanish across the elementary grades (Mora & Dorta-Duque de Reyes, in press).

Different Perspectives on the Role of Explicit Phonics Instruction

There are several areas of controversy surrounding the role of explicit phonics instruction in the literacy instruction for multilingual learners, most especially those who are classified as English learners because of their levels of English language proficiency (Umansky & Reardon, 2014). There are differing opinions about the meaning of the term “explicit” in relationship to phonics instruction (Burkins & Yaris, 2014; Ruetzel, et al., 2014, Torgerson, 2019: Villaume & Brabham, 2003). Torgerson (2019) makes the following observation:

“In the initial teaching of reading in languages with highly consistent orthographies (e.g., Spanish and especially Finnish), phonics is used without comment or dispute as the obvious way to give children who are not yet reading the most effective method of ‘word attack’, identifying unfamiliar printed words. The teaching of early reading in English, by contrast, has been highly politicised and is contentious, largely because of its notoriously complex set of grapheme-phoneme correspondences. (p. 209)”

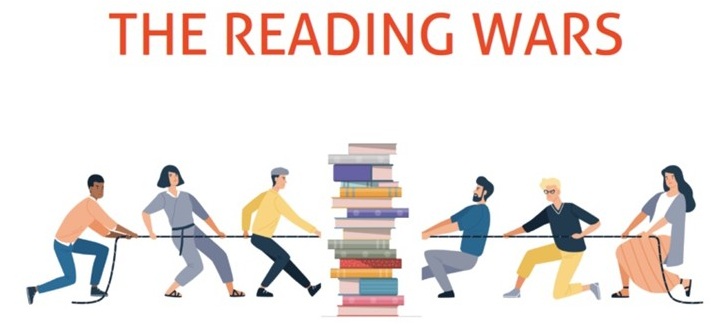

The controversy of a supposed “dosage” of phonics instruction is found in research that attempts to quantify the number of hours of phonics instruction necessary for students’ mastery of phonics subskills such as phonemic awareness (Erbeli, 2024, Mesmer, & Griffith, 2005). However, a framing of the controversy surrounding phonics as the core of literacy instruction is encapsulated below as a dichotomy: Are authentic literacy experiences through reading and writing merely supplemental versus reading and writing activities with authentic text as the core and explicit phonics instruction to supplemental (Ginns, et al, 2019; Rayner, et al., 2001)? Rayner et al. (2019) use the term “whole language activities to refer to authentic reading experiences.

We do not deny the value inherent in various principles of whole-language teaching methods. As we noted many times throughout this mono graph, instructional techniques that move beyond phonics practice to ensure the application of alphabetic principles to reading clearly support the process of learning to read. We also emphasized that the child’s learning is every bit as important as the teacher’s instruction. Obviously, using whole-language activities to supplement phonics instruction helps make reading fun and meaningful for children. Such activities may be most beneficial to children from environments where reading is not highly valued. But, at the end of the day, phonics instruction is critically important because it does help the beginning reader understand the alphabetic principle and apply it to reading and writing. Thus, the empirical data clearly indicate that elementary teachers who make the alphabetic principle explicit are most effective in helping their students become skilled, independent readers. (p. 68)

This statement raises the question: Why is it suggested that “whole-language activities” supplement phonics instruction instead of phonics instruction supplementing whole-language activities? Click to see further discussion of the scientific research on the effectiveness of methods of instruction for supporting and enhancing the literacy learning of multilingual learners below in the analysis of Tierney and Pearson’s (2024) Claim 7: Approaches and Methods.

Implications for Multilingual Learners’ Literacy Instruction

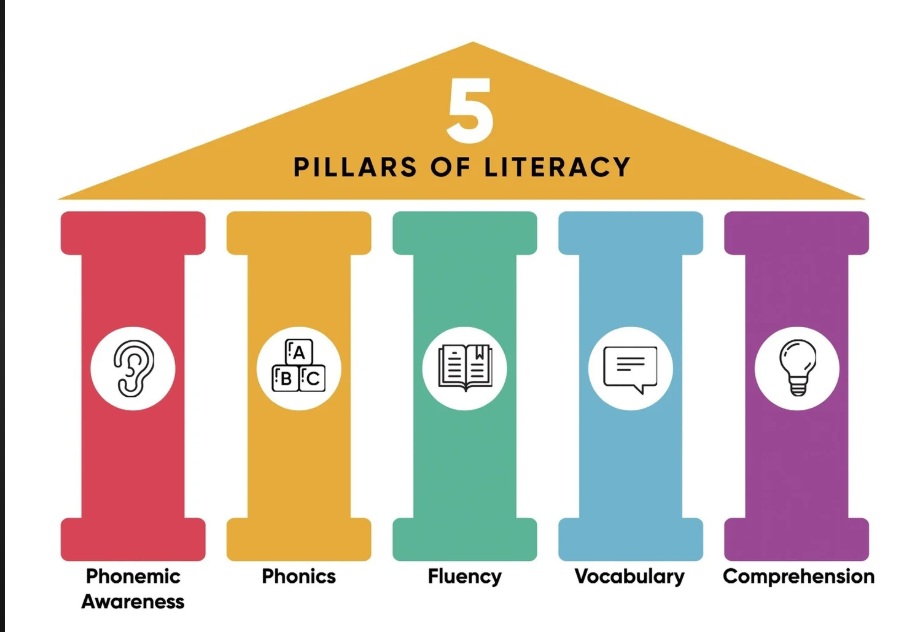

The National Reading Panel Report (2000) highlighted five “pillars” of reading instruction: phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency and comprehension. Sic years later, the National Literacy Panel on Language-minority Children and Youth that provided a meta-analysis of 293 studies from between 1980-2002 that focused on factors that influence language minority students’ second-language literacy development and achievement (August & Shanahan, 2006). These factors included individual differences in second-language oral proficiency, first-language oral proficiency and literacy, some socio-cultural variables, and classroom and school factors. The National Literacy Panel asserted that language-minority students are subject to an additional set of intervening influences related to their language proficiency and literacy in their first language and their socio-cultural context for literacy learning that were not addressed in the National Reading Panel Report (2000). The research on literacy instruction for emergent bilingual and English learners cannot be comprehensive and complete without considering the findings and conclusions of the National Literacy Panel (August & Shanahan, 200&) that employed a multidimensional, dynamic framework on native language and second-language literacy development. Also, consideration must be given to the research on Spanish literacy instruction from Spanish-speaking countries. See Dr. Mora’s Spanish Literacy Research bibliography available on the MoraModules website.

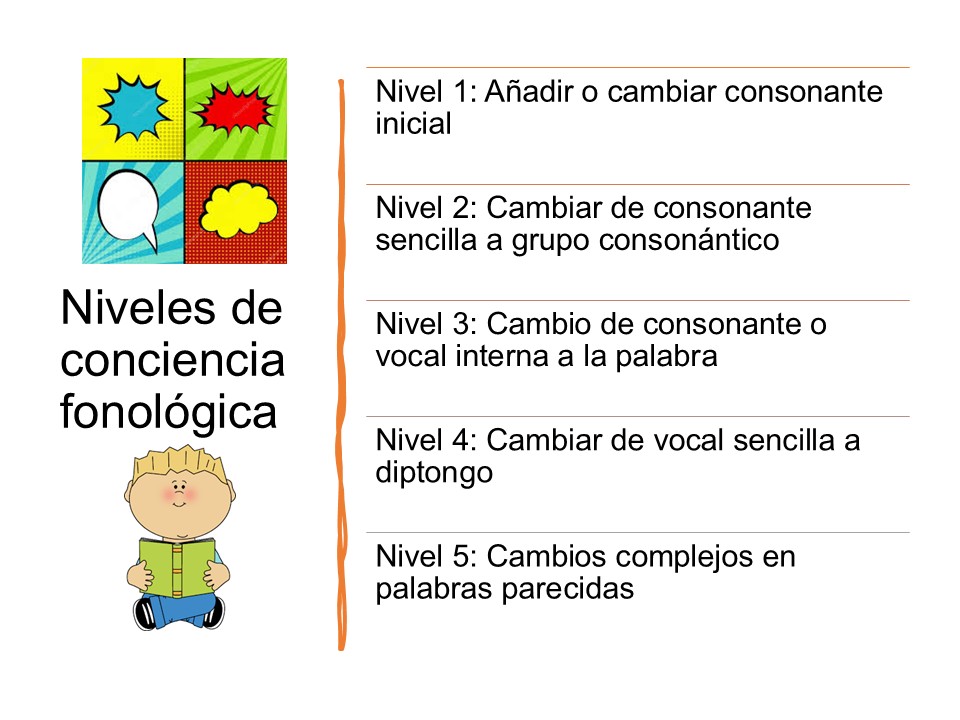

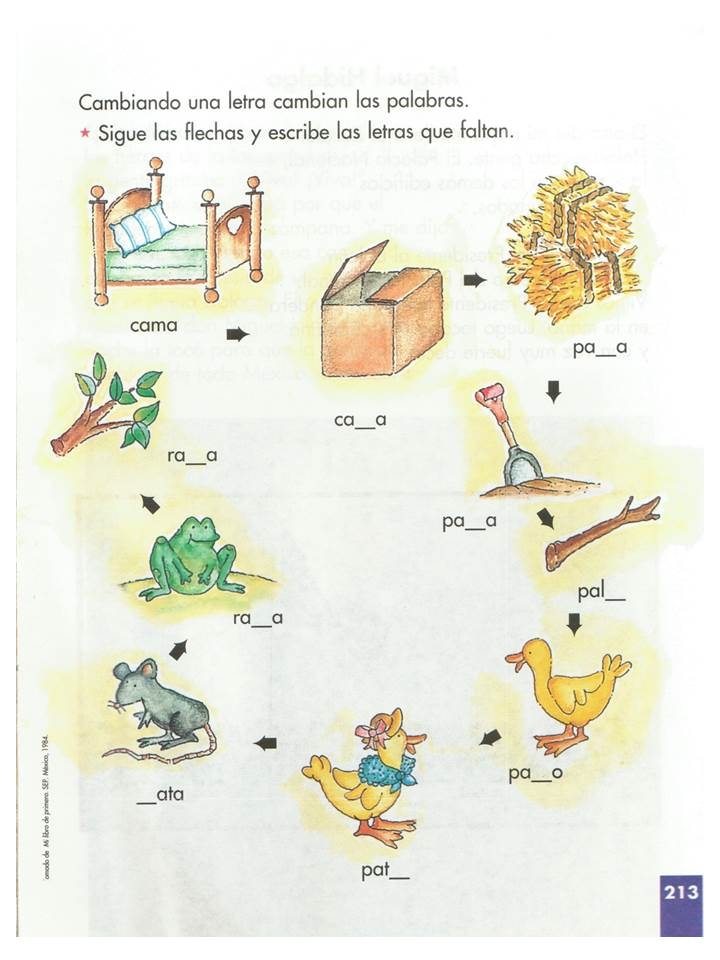

In a dual language program where students are learning language and literacy in two languages in tandem, the commonalities and contrasts between Spanish and English phonology compel decision making regarding the scope and sequence of instruction across the grades in the target and partner languages and the degree of focus on developing language-specific metalinguistic knowledge. Decision making in this area is based on the realization that phonological awareness and its subset, phonemic awareness are a metalinguistic skill that is transferable (Cárdenas-Hagan, et al, 2007; Koda & Reddy, 2008)). The processes of synthesis and analysis involved in developing an awareness of how sounds are manipulated to convey meaning is universally applicable to any language. The idea is this: When phonological awareness is taught in Spanish, the awareness that awareness of the sounds of Spanish. So the sound system that the learning about language-specific (Signorini, & Borzone de Manrique, 2003). Phonological abilities include explicit analysis and manipulations of linguistic sound units through matching of same phonemes, segmenting and blending, substitution of sounds in words, and isolation and/or deletion of phonemes within words (Mora, 2016).

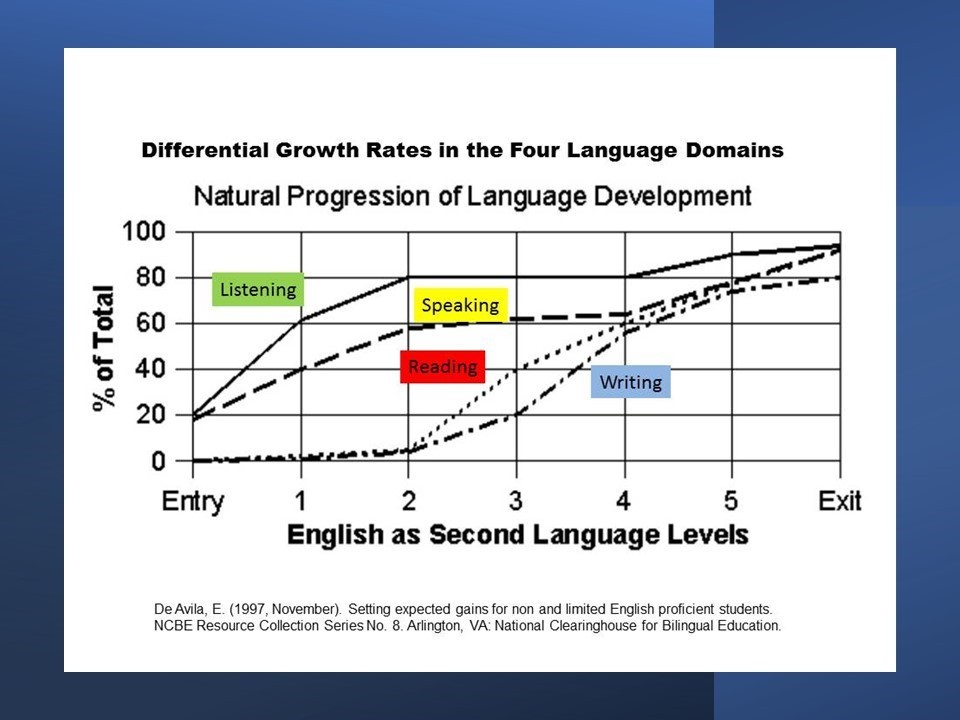

English learners who are not literate in their first or primary language (L1) and are in English-medium classrooms may need to develop phonological awareness of English phonemes and blends that do not exist in their L1, such as English vowel sounds (Anthony, et al., 2009; Fabiano, et.al, 2010). They also may need explicit instruction in English spelling patterns such as blends, digraphs, silent-e patterns, etc. (Goodrich & Lonigan, 2016; Zutell & Allen, 1998). It is essential to consider these learners’ English oral language proficiency when assessing their progress in literacy learning since expected gains in the four domains of the language arts (listening, speaking, reading, and writing) exhibit different learning curves according to L2 language proficiency (Ardasheva, et al., 2012; De Avila, 1997; Thompson, 2017; Umansky & Reardon, 2014).

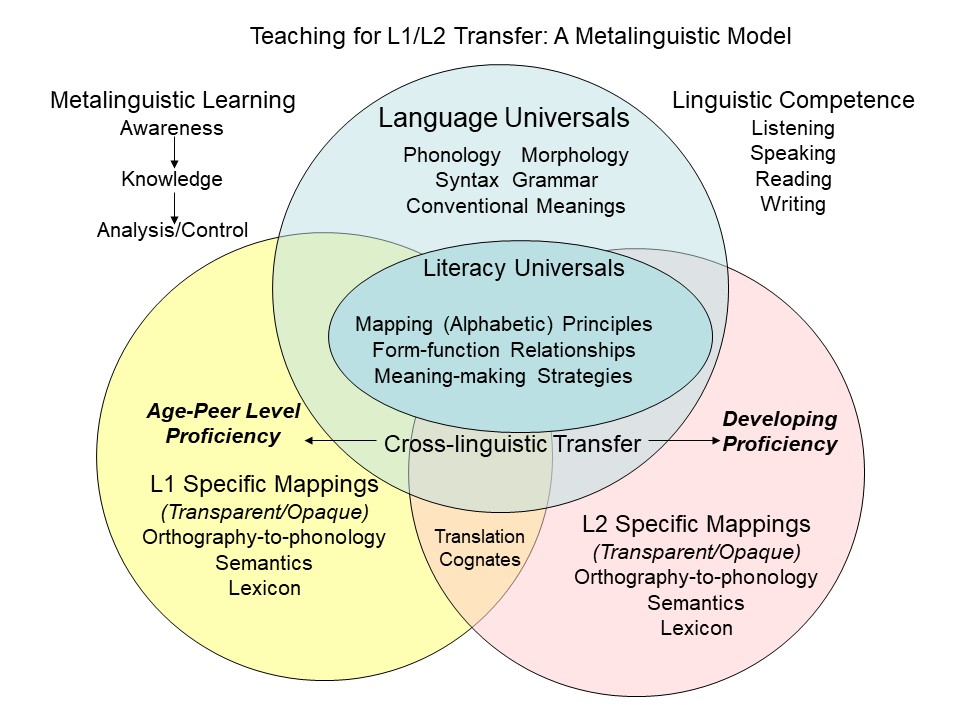

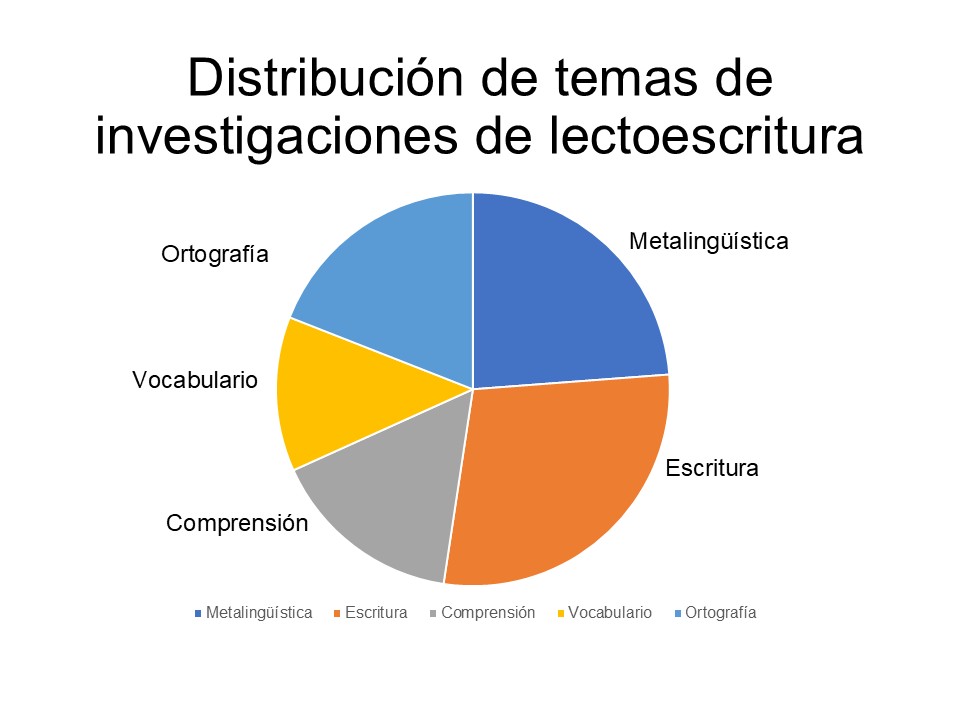

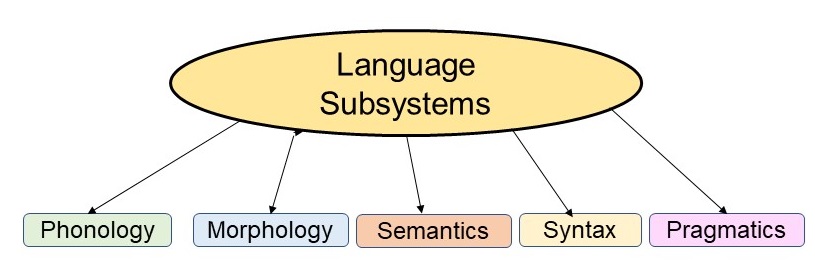

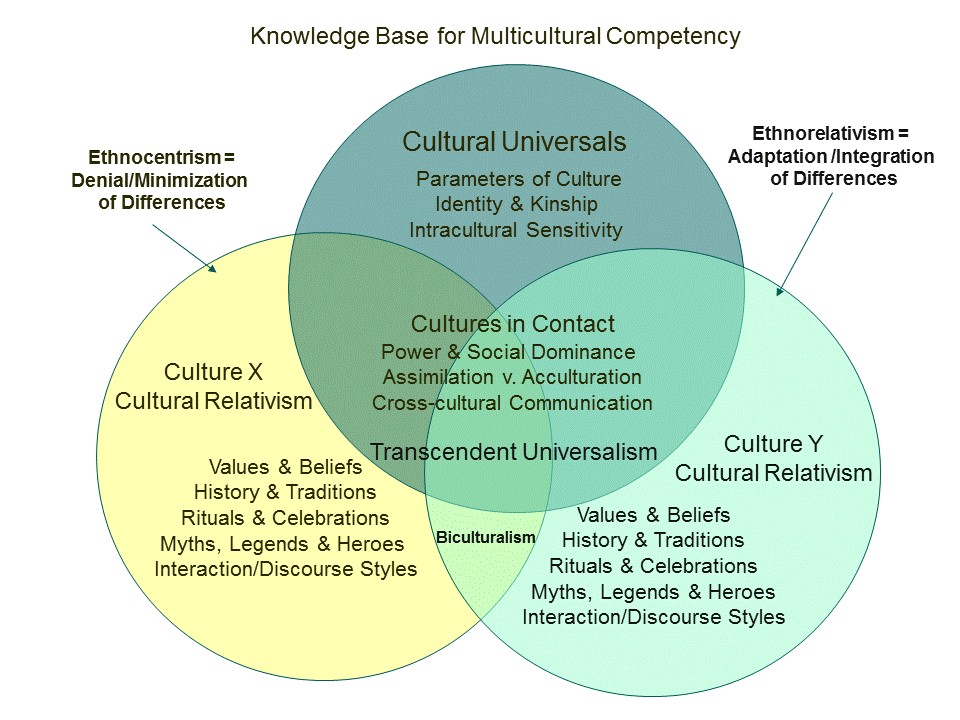

The foundational research on literacy acquisition in Spanish focuses on metalinguistic awareness and knowledge development. The progression of metalinguistic knowledge development in Spanish literacy learning is based on the features of the language-specific characteristics (forms and functions) of the subsystems of language: phonology, morphology, semantics, syntax, and pragmatics (Koda & Reddy, 2008). Effective literacy instruction for emergent bilingual learners requires teachers to make the distinction is made between language and literacy universals and language-specific features of the language of the text that students are reading and writing. A metalinguistic transfer facilitation approach to language and literacy instruction is recommended for emergent bilingual learners (Ke, Zhang & Koda, 2023).

REFERENCES Claim 1

Anthony, J. L., Solari, E. J., Williams, J. M., Schoger, K. D., Zhang, Z., Branum-Martin, L., & Francis, D. J. (2009). Development of bilingual phonological awareness in Spanish-Speaking English language learners: The roles of vocabulary, letter knowledge, and prior phonological awareness. Scientific Studies of Reading, 13(6), 535-564.

Antropova, S., Carrasco Polaino, R., & Anguita Acero, J. (2023). Synthetic phonics in Spanish bilingual education: Spelling mistakes analysis [Synthetic phonics en la enseñanza bilingüe en España: Análisis de errores ortográficos]. Porta Linguarum, 39(January), 299-314.

Alegría, J., & Carrillo, M. S. (2014). La escritura de palabras en castellano: Un análisis comparativo [Learning to spell words in Spanish: A comparative analysis]. Estudios de Psicología, 35(1), 476-501.

Apel, K. (2022). A different view on the Simple View of Reading. Remedial and Special Education, 43(6), 434-447.

Apel, K. (2011). What is orthographic knowledge. Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 42(October), 592-603.

Ardasheva, Y., Tretter, T. R., & Kinny, M. (2012). English language learners and academic achievement: Revisiting the threshold hypothesis. Language Learning, 62(3), 768-812.

Burkins, J., & Yaris, K. (2014). Breaking through the frustration: Balance vs. all-or-nothing thinking. Reading Today, September/October, 26-27.

Cano Muñoz, S., & Vernon, S. A. (2008). Denominación y uso de los consonantes en el proceso inicial de alfabetización. Lectura y Vida, 29(2), 32-45.

Cárdenas-Hagan, E., Carlson, C. D., & Pollard-Durodola, S. D. (2007). The cross-linguistic transfer of early literacy skills: The role of initial L1 and L2 skills and language of instruction. Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, July, 249-259.

Clemente Linuesa, M., & Rodríguez Martín, I. (2014). Enseñanza inicial de la lengua escrita: De la teoría a la práctica [Initial teaching of written language: From theory to practice]. Aula, 20, 105-122.

De Avila, E. (1997). Setting expected gains for non and limited English proficient students. Nassaji, H. (2006). The relationship between depth of vocabulary knowledge and L2 learners’ lexical inferencing strategy use and success. The Modern Language Journal, 90(3), 387-401. Arlington, VA: National Clearinghouse for Bilingual Education.

Dehaene, S. (2015). Aprender a leer: De las ciencias cognitivas al aula [Learning to read: From the cognitive sciences to the classroom]. Siglo Veintiuno Editores.

Dehaene, S. (2014). El cerebro lector [The reading brain]. Siglo Veintiuno Editores.

DeKeyser, R. (2003). Implicit and explicit learning. In C. J. Doughty & M. H. Long (Eds.), The handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 313-348). John Wiley & Sons.

Ellis, R. (2005). Measuring implicit and explicit knowledge of a second language: A psychometric study. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 27, 141-172.

Erbeli, F., Rice, M., Xu, Z., Bishop, M. E., & Goodrich, J. M. (2024). A meta-analysis on the optimal cumulative dosage of early phonemic awareness instruction. Scientific Studies of Reading, 28(4), 345-370.

Escamilla, K., Andrade, A. M., Basurto, A. G., & Ruiz, O. A. (1996). Instrumento de observación de los logros de la lecto-escritura inicial [Spanish reconstruction of an observation survey of early literacy achievement by Marie Clay]. Heinemann.

Fabiano-Smith, L., & Goldstein, B. A. (2010). Phonological acquisition in bilingual Spanish-English speaking children. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 53(February), 160-178.

Fedeli, D., Del Maschio, N. S., Simone, Rothman, J., & Abutalebi, J. (2021). The bilingual structural connectome: Dual-language experiential factors modulate distinct cerebral networks. Brain and Language, 220(104978), 1-11.

Ferreiro, E. (2009). The transformation of children’s knowledge of language units during beginning and initial literacy. In J. V. Hoffman & Y. M. Goodman (Eds.), Changing literacies for changing times: An historical perspective on the future of reading research, public policy, and classroom practices (pp. 61-75). Taylor & Francis Group.

Ferreiro, E., & Teberosky, A. (1979). Los sistemas de escritura en el desarrollo del niño. Siglo Ventiuno Editores.

Flores, B. (2025). Biliteracy con cariño: Using interactive dialogue journals as a bridge to proficient reading while writing in L1 and L2. California Association for Bilingual Education.

Francis, N. (2011). Bilingual competence and bilingual proficiency in child development. MIT Press.

Francis, W. S., Strobach, E. N., Penalver, R. M., Martínez, M., Gurrola, B. V., & Soltero, A. (2019). Word-context associations in episodic memory are learned at the conceptual level: Word frequency, bilingual proficiency, and bilingual status effects on source memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 45(10), 1852-1871.

Freeman, Y. S., & Freeman, D. E. (2009). La enseñanza de la lectura y la escritura en español y en inglés en clases bilingües y de doble inmersión (2da ed.). Heinemann.

Frost, R. (2012). Towards a universal model of reading. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 35, 263-329. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X11001841

Gil, J. M. (2019). Lectoescritura como sistema neurocognitivo [Reading and writing as a neurocognitive system]. Educación y Educadores, 22(3), 422-447.

Ginns, D., Joseph, L. M., Tanaka, M. L., & Xia, Q. (2019). Supplemental phonological awareness and phonics instruction for Spanish-speaking English Learners: Implications for school psychologists. Contemporary School Psychology, 23, 101-111.

Goldenberg, C., Tolar, T. D., Reese, L., Francis, D. J., Bazán, A. R., & Mejía-Arauz, R. (2014). How important is teaching phonemic awareness to children learning to read in Spanish? American Education Research Journal, 51(3), 604-633. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831214529082

Goodrich, J. M., & Lonigan, C. J. (2016). Lexical characteristics of Spanish and English words and the development of phonological awareness skills in Spanish-speaking language-minority children. Reading & Writing, 29, 683-704.

Haastrup, K. (2009). Research on the lexical inferencing process and its outcomes. In M. B. Wesche & T. S. Paribakht (Eds.), Lexical inferencing in a first and second language: Cross-linguistic dimensions (pp. 3-30). Multilingual Matters.

Jiménez, J. E., & Ortiz, M. R. (2000). Metalinguistic awareness and reading acquisition in the Spanish language. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 3(001), 37-46.

Ke, S. E., Zhang, D., & Koda, K. (2023). Metalinguistic awareness in second language reading development. Cambridge University Press.

Kovelman, I., Din, M. S.-U., Berens, M. S., & Petitto, L. A. (2015). “One glove does not fit all” in bilingual reading acquisition: Using the age of first bilingual language exposure to understand optimal contexts for reading success. Cogent Education, 2: 1006504, 1-12.

Jiménez, R. T., García, G. E., & Pearson, P. D. (1996). The reading strategies of bilingual Latina/o students who are successful English readers: Opportunities and obstacles. Reading Research Quarterly, 31(1), 90-112.

Koda, K., & Reddy, P. (2008). Cross-linguistic transfer in second language reading. Language Teaching, 41(4), 497-508.

Margarito Gaspar, M., & Margarito Gaspar, U. (2023). Los enfoques para la enseñanza de la lectoescritura en los últimos 30 años de México [The approaches to literacy teaching for the last 30 years in Mexico]. Revista Internacional de Aprendizaje, 10(1), 1-21.

Marks, R. A., Satterfield, T., & Kovelman, I. (2022). Integrated multilingualism and bilingual reading development. In J. MacSwan (Ed.), Multilingual perspectives on translanguaging (pp. 201-223). Multilingual Matters.

Mena Andrade, S. (2020). Enseñanza del código alfabético desde la ruta fonológica [Instruction of the alphabetic code through the phonological route]. Revista Andina de Educación, 3(1), 2-7. https://doi.org/10.32719/26312816.2020.3.1.1

Mesmer, H. A., & Griffith, P. L. (2005). Everybody’s selling it–But just what is explicit, systematic phonics instruction? The Reading Teacher, 59(4), 366-376.

Mora, J. K. (2016). Spanish language pedagogy for biliteracy programs. Montezuma Publishing.

Mora, J.K. (2001). Learning to spell in two languages: Orthographic transfer in a transitional Spanish/English bilingual program. In P. Dreyer (Ed.), Raising Scores, Raising Questions: Claremont Reading Conference 65th Yearbook (pp. 64-84). Claremont, CA: Claremont Graduate University.

Mora, J. K., & Dorta-Duque de Reyes, S. (in press). Biliteracy and cross-cultural teaching: A framework for standards-based transfer instruction in dual language programs. Brookes Publishing.

Nassaji, H. (2006). The relationship between depth of vocabulary knowledge and L2 learners’ lexical inferencing strategy use and success. The Modern Language Journal, 90(3), 387-401.

Padrón, Y. N. (1992). The effect of strategy instruction on bilingual students’ cognitive strategy use in reading. Bilingual Research Journal, 16(3-4), 35-51.

Petitto, L. A., Berens, M. S., Kovelman, I., Dubins, M. H., Jasinska, K. K., & Shalinsky, M. (2012). The “perceptual wedge hypothesis” as the basis for bilingual babies’ phonetic processing advantage: New insights from fNIRS brain imaging. Brain and Language, 121(2), 130-143.

Pollard-Durodola, S. D., & Simmons, D. C. (2009). The role of explicit instruction and instructional design in promoting phonemic awareness development and transfer from Spanish to English. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 25, 139-161.

Raudszus, H., Segers, E., & Verhoeven, L. (2021). Use of morphological and contextual cues in children’s lexical inferencing in L1 and L2. Reading & Writing, 34, 1513-1538.

Rayner, K., Foorman, B. R., Perfetti, C. A., Pesetsky, D., & Seidenberg, M. S. (2001). How psychological science informs the teaching of reading. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 2(2), 31-74.

San Diego County Office of Education (2012). Common Core State Standards: English/Spanish Language Version. Washington, D.C.: Council of Chief State School Officers

Seidenberg, M. S. (2013). The science of reading and its educational implications. Language Learning & Development, 9(4), 331-36.

Signorini, A., & Borzone de Manrique, A. M. (2003). Aprendizaje de la lectura y escritura en español: El predominio de las estrategies fonológicas [Learning to read and spell in Spanish. The prevalence of phonological strategies]. Interdisciplinaria, 20(2), 5-30.

Share, D. L. (2025). Blueprint for a universal theory of learning to read: The combinatorial model. Reading Research Quarterly, 60, e603. https://doi.org/doi:10.1002/rrq.603

Share, D. (2004). Orthographic learning at a glance: On the time course and developmental onset of self-teaching. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 87, 267-298.

Sharwood Smith, M. (2021). The cognitive status of metalinguistic knowledge in speakers of one or more languages. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 24, 185-196. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728920000371

Smith, A. C., Monaghan, P., & Huettig, F. (2021). The effect of orthographic systems on the developing reading system: Typological and computational analyses. Psychological Review, 128(1), 125-159.

Soto, X. O., Arnold, & Goldstein, H. (2019). A systematic review of phonological awareness interventions for Latino children in early and primary grades. Journal of Early Intervention, 41(4), 340-365.

Templeton, S. (2025). The implications and applications of developmental spelling after phonics instruction. Education Sciences, 15(195), 1-19.

Thompson, K. D. (2017). English learners’ time to reclassification: An analysis. Educational Policy, 31(3), 330-363.

Tolchinsky, L. (1990). Lo práctico, lo científico y lo literario: Tres componentes en la noción de alfabetismo [The practical, the scientific and the literary: Three components to the notion of alphabetism (literacy)]. Comunicación, Lenguaje y Educación, 6, 53-62.

Torgerson, C. (2019). Phonics: Reading policy and the evidence of effectiveness from a systematic “tertiary” review. Research Papers in Education, 34(2), 208-238.

Umansky, I. M., & Reardon, S. (2014). Reclassification patterns among Latino English learner students in bilingual, dual immersion, and English immersion classrooms. American Education Research Journal, 51(5), 879-912.

Vernon, S. A. (2007). The effect of writing on phonological awareness in Spanish. In M. Torrance, L. van Waes, & D. Galbraith (Eds.), Writing and cognition: Research and applications (Vol. 20, pp. 181-199). Elsevier Ltd.

Villaume, S. K., & Brabham, E. G. (2003). Phonics instruction: Beyond the debate. The Reading Teacher, 56(5), 478-482.

Wheldall, K., Wheldall, R., Bell, N., & Buckingham, J. (2020). Researching the eficacy of a reading intervention: An object lesson. The Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 37, 147-151.

Wesche, M. B., & Paribakht, T. S. (Eds.). (2009). Lexical inferencing in a first and second language: Cross-linguistic dimensions. Multilingual Matters.

Zutell, J., & Allen, V. (1988). The English spelling strategies of Spanish-speaking bilingual children. TESOL Quarterly, 22(2), 333-340.

SoR CLAIM 2

The Simple View of Reading provides an adequate theoretical account of skilled reading and its development over time.

Tierney, R. J., & Pearson, P. D. (2024). Fact-checking the Science of Reading: Opening up the conversation. Literacy Research Commons.

The Simple View of Reading proposes that reading is the product of decoding and listening or linguistic comprehension. Decoding, in this model, refers to the ability to obtain a representation from print to remember the meaning of a word. Language comprehension refers to the ability to take the meaning of words to obtain meaning at the sentence and word level of input that have been presented orally. Reading comprehension requires the combination of both processes to derive meaning from text (Hoover & Gough, 1990). The “language comprehension” component of the Simple View of Reading states a formula to describe the process required for reading comprehension: “Decoding X Language Comprehension = Reading Comprehension.” The Simple View of Reading is based on this definition of decoding:

Decoding: For the simple view, skilled decoding is simply efficient word recognition: the ability to rapidly derive a representation from printed input that allows access to the appropriate entry in the mental lexicon, and thus, the retrieval of semantic information at the word level. (p. 130)

Nonetheless, the result is important in demonstrating the separate contributions of decoding and linguistic comprehension to reading ability, as the trend is consistent with the view that for skilled reading, skill in both components is required, while a weakness in either component is sufficient for less skilled reading. (p. 147)

Under the simple view of reading, linguistic comprehension and reading comprehension in this individual are equivalent; with respect to current linguistic skill, such a person is fully literate (for reading) since whatever can be comprehended by ear can likewise be comprehended by eye, and vice versa. Simply increasing the decoding skill of such an individual will not increase reading comprehension as the meaning of any words that can now be decoded given the newly expanded skill will still be absent from the internal lexicon. (p. 155)

Hoover and Tunmer (2018) provide a comprehensive perspective on how the Simple View of Reading informs literacy learning trajectories across the grades.

So what are the main conclusions we can draw from the three studies just reviewed? First, based on the benefits provided by latent variable modeling, the SVR continues to provide a robust description of reading comprehension for children in Grades 3 to 5, with word recognition and language comprehension capturing almost all of the variance in reading comprehension. The small amounts of remaining variance suggest that if there are other factors involved in reading, they will make relatively small contributions as proximal factors, or as distal ones they will likely operate through word recognition or language comprehension. Second, the two main component skills in reading at these later grades are substantially related to such skills in earlier grades, indeed as early as prekindergarten. Third, the contributions of word recognition and language comprehension vary with grade level, with word recognition generally making stronger contributions in the earlier grades and language comprehension in the later grades. Fourth, there are large amounts of shared variance between word recognition and language comprehension, and understanding the source of this overlap has important consequences for thinking about instructional interventions.

In an analysis of the Simple View of Read, Apel (2022) states the following:

By definition, oral or spoken language is the ability to produce and comprehend speech through the spontaneous interactive use of five knowledge bases—phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics—during a communicative exchange. (p. 435)… Regardless of whether the linguistic comprehension tasks were labeled as listening or language comprehension measures, and irrespective of whether the task(s) used to assess linguistic comprehension mirrored the reading comprehension task(s) administered, the findings across nearly all studies guided by the SVR model have been similar; the researchers’ measures of decoding and linguistic comprehension explained a large amount of variance on their measure(s) of reading comprehension. This, then, begs the question, “What do all of the listening and language comprehension tasks have in common?” Put another way, “What explains the agreement in findings based on such disparate tasks and differing methods?” One might claim that the two questions are moot. Regardless of inconsistencies, some measure(s) labeled as assessing listening or language comprehension, along with a measure(s) of decoding explained a large amount of performance on a reading comprehension task(s). (p. 438)

Apel (2022:442) makes the connection between metalinguistic knowledge and accounts of reading comprehension abilities. He concludes that the evidence from different lines of research demonstrates the important contributions of multiple metalinguistic skills (e.g., phonological awareness, morphological awareness, syntactic awareness) to reading comprehension. Therefore, instruction that includes a focus on these multiple language awareness skills is required.

Cervetti, et al. (2020: S161) on be half of the Reading for Understanding Initiative, describe reading comprehension as “… a complicated constellation of skills and knowledge...” that is not reflected in the Simple View of Reading. These researchers criticize the Science of Reading advocates for not giving sufficient attention to the research evidence of the significance of listening comprehension in young readers and the importance of early oral language skills that support both decoding and listening comprehension.

half of the Reading for Understanding Initiative, describe reading comprehension as “… a complicated constellation of skills and knowledge...” that is not reflected in the Simple View of Reading. These researchers criticize the Science of Reading advocates for not giving sufficient attention to the research evidence of the significance of listening comprehension in young readers and the importance of early oral language skills that support both decoding and listening comprehension.

Foorman and Petscher (2018) argue the following regarding the Simple View of Reading:

Conceptually it makes sense that decoding and linguistic comprehension would share variance in predicting written language because word recognition entails the linguistic skills of levels phonology, semantics, and discourse at the sentence and text levels. Similarly, linguistic comprehension must be connected to orthographic representations of phonemes, morphemes, words, sentences, and discourse if text is to be understood. Regression results for linguistic comprehension showed a fairly constant picture of L contributing substantial proportions of variance to reading comprehension across the grades, 36% in grade 1 to 54% in grade 10. However, when the method of decomposing the variance was used, the unique contribution of linguistic comprehension over the grades showed a dramatic increase from 17% in grade 1 to 28% in grade 7, to 42% in grade 10. The amount of common variance that decoding and linguistic comprehension together explain in predicting reading comprehension, especially in the elementary grades, suggests that more instructional emphasis should be placed on the integration of linguistic knowledge at the word level.

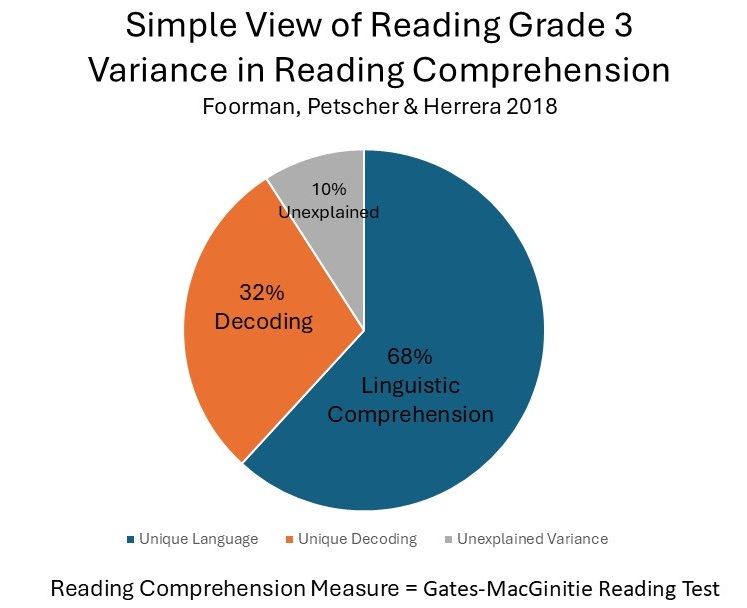

Foorman, Petscher and Herrera (2018) describe the percentages of variance in reading comprehension that make unique contributions to total scores on comprehension assessments in third grade. Research on literacy development of multilingual learners reading in their second language based on the Simple View of Reading (SVR) finds that the most salient obstacles to reading comprehension for English learners are not decoding skills, but rather, are linguistic comprehension factors (Cho, et al., 2019; Jeon & Yamashita, 2014). Jeon and Kamashito define decoding as a process during which a reader converts letters (graphemes) to sounds (phonemes) and, essentially, to language. In a meta-analysis of research on the Simple View of Reading theoretical framework, these researchers found that overall, the developmental pattern of young L2 readers’ decoding ability and its relationship with reading largely mirror that of L1 children with only a slight delay or with an almost synchronous rate. Jeon and Yamashita (2014) found in a meta-analysis of SVR that the variance in comprehension measures for English Learners was attributable to second language (L2) grammar knowledge (72%) and L2 vocabulary knowledge (62%), while language-general variables and decoding were low-evidence coordinates.

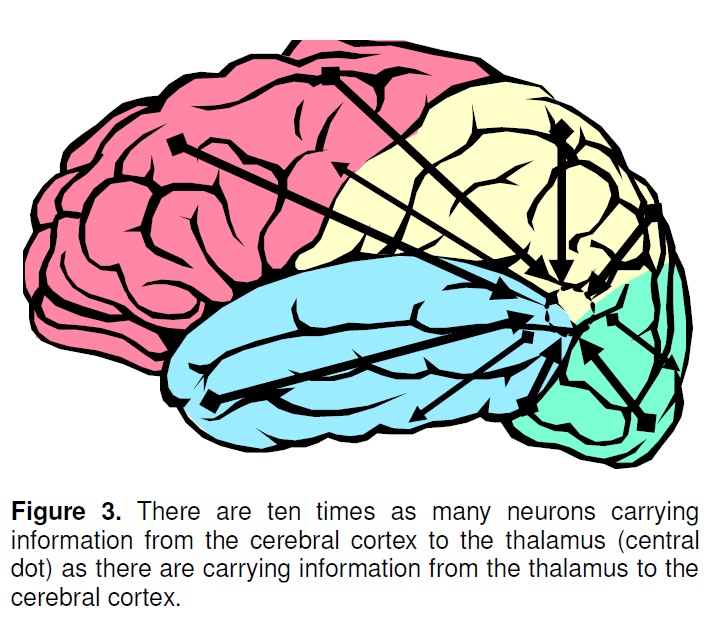

Duke and Cartwright (2021) propose the Active View of Reading Model that is supported by a review of four categories and 18 discrete constructs found in the research literature to unpack the range of contributors to the reading process. (See Duke & Cartwright, Table 2, p. 535-536). While many of these constructs apply equally to monolingual readers of English, this researcher identifies constructs that may have both a universal application across monolingual readers and bilingual/multilingual language learners and readers that are specific to the native or first language of the learners and the language of the text in which they are reading and writing. In the Active View of Reading Model, the construct of active self-regulation is found in research on Spanish monolingual readers and research with emergent Spanish-English bilingual readers to vary in the neurocognitive aspects of executive function due to different pathways and connectors between languages in the bilingual brain (Arredondo, et al., 2017; Dijkstra & van Heuven, 2002; Hoversten & Traxler, 2020; León Cascón, 2009). The development of current and more comprehensive models of reading contributes to researchers deeper understanding of the commonalities and differences between monolingual and multilingual literacy acquisition.

Implications of SVR for Multilingual Learners

The obvious conclusion that must be drawn from a coherent view of reading is that the same knowledge and skills are necessary for comprehending the language of a written text as are required for comprehending speech orally. To understand speech, the listener must understand the semantics meaning of the words used by the speaker. Many of these words have meanings that depend on the linguistic context in which they are used. This context includes the syntax of the phrase or sentence in which the word is used. Words are not understood in isolation in the flow of speech. This is the essence of the Simple View of Reading. Many experienced teachers use a mode of assessment called an informal reading inventory (Ascenzi-Moreno, 2016; Kabuto, 2016; Vehoeven, et al., 2019). A part of an informal reading assessment is to read a passage to a student and then ask comprehension questions about the passage. If the student can understand the language of the passage read orally, then the probability that s/he can decode the passage is high. The teacher is engaging in assessment practices to discern the correlation between a student’s listening comprehension and his/her reading comprehension. Thus, this assessment procedure is an enactment of the Simple View of Reading.

As teachers of students who are second language learners of English and are in the process of learning to comprehend oral English, teachers need to be knowledgeable about semantics as vocabulary knowledge. This involves an understanding of the grammatical and syntactic meaning and functions of words within sentences and discourse, the whole linguistic context of written text. The broader implication of the Simple View of Reading is this: Whatever the learner learns that enhances linguistic comprehension, also enhances decoding, and vice versa. Whatever the learner learns that enhances decoding, enhances linguistic comprehension. These two components are not in competition with each other. The notion that instruction in meaning-making strategies “dilutes” decoding instruction is logically incoherent. Consequently, attempts to discredit or ban instructional strategies that focus on prompting students to focus on any of the subsystems of language.

REFERENCES Claim 2

Apel, K. (2022). A different view on the Simple View of Reading. Remedial and Special Education, 43(6), 434-447.

Arredondo, M. M., Hu, X.-S., Satterfield, T., & Kovelman, I. (2017). Bilingualism alters children’s frontal lobe functioning for attentional control. Developmental Science, 20, e12377.

Ascenzi-Moreno, L. (2016). An exploration of elementary teachers’ views of informal reading inventories in dual language bilingual programs. Literacy Research and Instruction, 44(4), 285-308. http://academicworks.cuny.edu/bc_pubs/101.

Cervetti, G. N., Pearson, P. D., Palincsar, A., Afflerbach, P., Kendeou, P., Biancarosa, G., Higgs, J., Fitzgerald, M. S., & Berman, A. I. (2020). How the Reading for Understanding Initiative’s research complicates the Simple View of Reading invoked in the Science of Reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(51), S161-S172.

Cho, E., Capin, P., Roberts, G., Roberts, G. J., & Vaughn, S. (2019). Examining sources and mechanisms of reading comprehension difficulties: Comparing English learners and non-English learners within the Simple View of Reading. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(6), 982-1000.

Duke, N. K., & Cartwright, K. B. (2021). The science of reading progresses: Communicating advances beyond the Simple View of Reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(S1), S25-S44. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.411

Foorman, B. R., & Petscher, Y. (2018). Decomposing the variance in reading comprehension to reveal the unique and common effects of language and decoding. Journal of Visualized Experiments, 140(October), e58557. https://doi.org/10.3791/58557

Foorman, B. R., Petscher, Y., & Herrera, S. (2018). Unique and common effects of decoding and language factors in predicting reading comprehension in grades 1-10. Learning and Individual Differences, 63, 12-23.

Hoover, W. A., & Gough, P. B. (1990). The Simple View of Reading. Reading and Writing, 2(2), 127-160.

Hoover, W. A., & Tunmer, W. E. (2018). The Simple View of Reading: Three assessments of its adequacy. Remedial and Special Education, 39(5), 304-312.

Hoversten, L. J., & Traxler, M. J. (2020). Zooming in on zooming out: Partial selectivity and dynamic tuning of bilingual language control during reading. Cognition, 195, 104118.

Jeon, E. H., & Yamashita, J. (2014). L2 reading comprehension and its correlates: A meta-analysis. Language Learning, 64(1), 160-212.

Kabuto, B. (2016). A socio-psycholinguistic perspective on biliteracy: The use of miscue analysis as a culturally relevant assessment tool. Reading Horizons, 56(1).

Kim, Y.-S. G. (2017). Why the Simple View of Reading is not simplistic: Unpacking component skills of reading using a direct and indirect effect model of reading (DIER). Scientific Studies of Reading, 21(4), 310-333.

León Cascón, J. A. (2009). Neuroimagen de los procesos de comprensión de la lectura y el lenguaje [Neuroimaging of the comprehension processes in reading and language]. Psicología Educativa, 15(1), 61-71.

Nation, K. (2019). Children’s reading difficulties, language, and reflections on the simple view of reading. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 24(1), 47-73. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404158.2019.1609272

Protopapas, A., Mouzaki, A., Sideridis, G. D., Kotsolakou, A., & Simos, P. G. (2013). The role of vocabulary in the context of the Simple View of Reading. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 29(2), 168-202.

Silva-Maceda, G., & Camarillo-Salazar. (2021). Reading comprehension gains in a differentiated reading intervention in Spanish based on the Simple View. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 37(1), 19-41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265659020967985

Verhoeven, L., Voeten, M., & Vermeer, A. (2019). Beyond the simple view of early first and second language reading: The impact of lexical quality. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 50, 26-36.

SoR CLAIM 3

Reading is the ability to identify and understand words that are part of one’s oral language repertoire.

Claim 3 Reading is the ability to identify and understand words that are part of one’s oral language repertoire.

Tierney, R. J., & Pearson, P. D. (2024). Fact-checking the Science of Reading: Opening up the conversation. Literacy Research Commons.

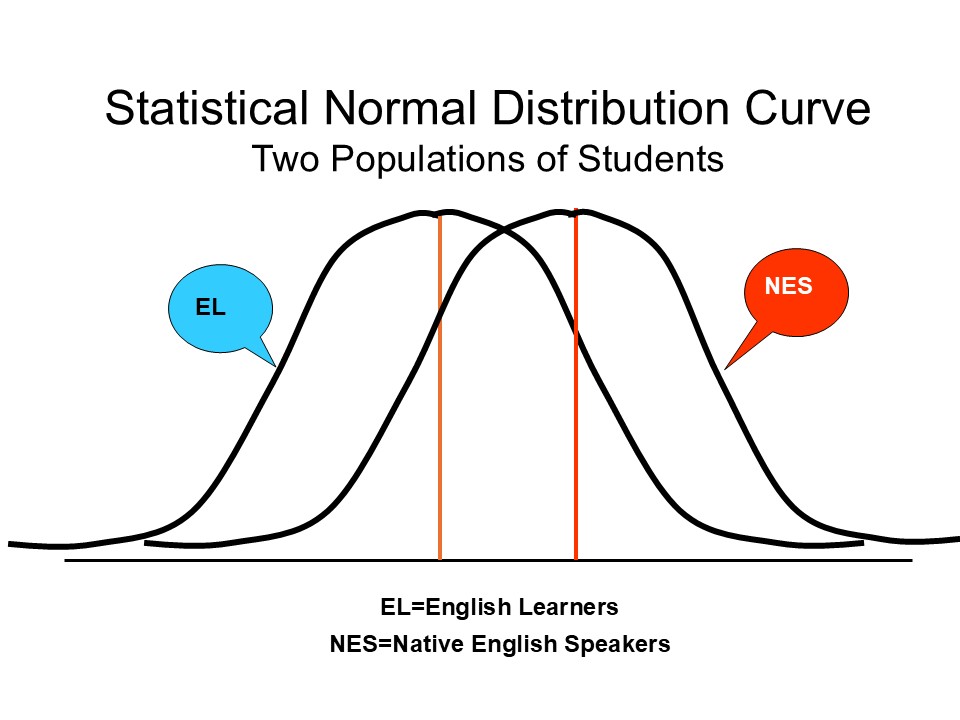

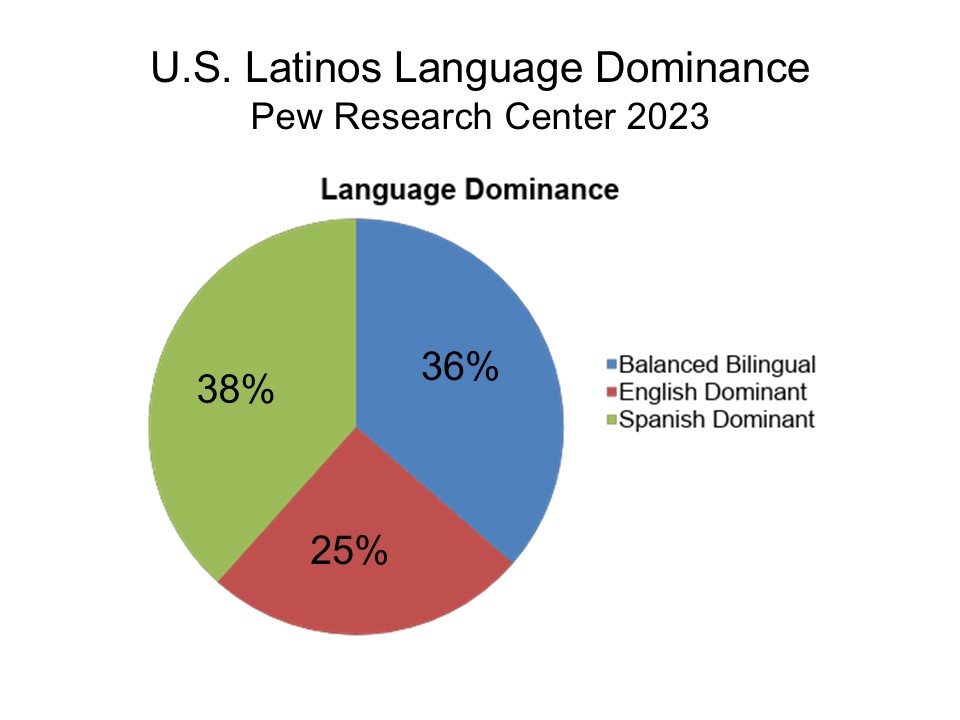

In their presentation of Claim 3 Tierney and Pearson emphasize the implications of narrow definitions of reading versus broader definitions of literacy. “We take this stance mainly because we believe that the narrow definition pushes most of the important variables in the quest for making meaning into another category—one we might label literacy and learning… Conversely, we see—and will try to convince readers of—the many advantages of a sociocultural model, especially on standards of ecological validity, diversity, and equity (p. 49). This focus on sociocultural factors in literacy learning is in keeping with the different perspective of research on literacy learning for students who are learning to read in a language in which they do not (yet) have a native-speaker equivalent proficiency.  The common term for identifying such students in public schools in the United States is English Learners (EL). However, when these students are enrolled in bilingual or dual language programs where they are acquiring a second language and biliteracy in tandem are called Emergent Bilinguals (EB). There are multiple research paradigms that investigate these students’ language and literacy learning characteristics and outcomes (Cummins, 2021; Koda, 2004; Mora, 2024). These include predominantly second-language acquisition research, second-language reading research and metalinguistics. The term multilingual learners is also commonly used to refer to students with different first other-than-English languages used in the home who may or may not be classified as English learners because of their proficiency levels in more than one language (Cummins, 2021).

The common term for identifying such students in public schools in the United States is English Learners (EL). However, when these students are enrolled in bilingual or dual language programs where they are acquiring a second language and biliteracy in tandem are called Emergent Bilinguals (EB). There are multiple research paradigms that investigate these students’ language and literacy learning characteristics and outcomes (Cummins, 2021; Koda, 2004; Mora, 2024). These include predominantly second-language acquisition research, second-language reading research and metalinguistics. The term multilingual learners is also commonly used to refer to students with different first other-than-English languages used in the home who may or may not be classified as English learners because of their proficiency levels in more than one language (Cummins, 2021).

Research in the field of second language acquisition (SLA) contributes a number of theories and constructs to the pedagogical knowledge base for literacy instruction for EL/EB students. Learning a new, second, foreign or additional language (L2) may be simultaneous or sequential, depending on the linguistic and cultural circumstances of the emergent bilingual student. SLA research provides knowledge of a sequence of learning through developmental levels that enable teachers to assess L2 language proficiency’s correlation with variability in students’ outcomes in literacy learning. The reciprocity of L2 language and literacy learning is confirmed through research that disaggregates factors within the learner’s common underlying reservoir of cross-linguistic interdependence (Cummins, 2021). Speaking develops more gradually through instruction scaffolded and differentiated to accommodate students’ language current proficiency level while challenging them to the next level of production and comprehension. Learners acquire language through making meaning of oral language that enables them to comprehend written text that they are able to decode fluently. Reading and writing skills are delayed as students acquire adequate listening comprehension and speaking fluency at an intermediate level of proficiency. Consequently, English Learners’ success in literacy learning depends upon their building a foundation of oral language and listening comprehension. Language skills for forming and parsing sentences such as syntax and grammar are crucial for developing decoding, reading fluency, and comprehension. In California, the English Language Arts/English Language Development Framework is the state’s policy document that guides standards-based instruction for English learners.

Second Language Acquisition and Literacy Learning

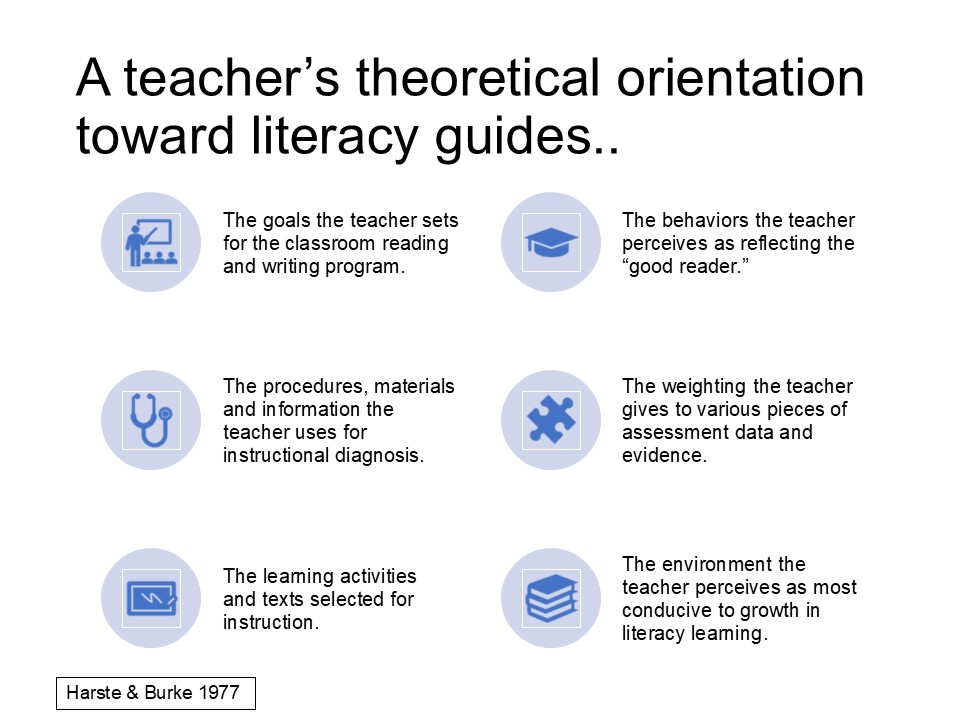

Professor Michael Halliday (1993) describes children’s language development as a process of construction based on the child’s need to convey meaning in social settings, with the structures of language, such as syntax, grammar and idiomatic expressions used as a means to achieve a communicative purpose. Upon entering school, children are expected to learn through language used as a medium of instruction in the classroom and of academic and literary text. In fact, language itself is treated as educational knowledge, as seen in the emergence in current pedagogy of the concept of “academic language.” Children begin to learn about language as the essentially unconscious and implicit nature of linguistic processes are made conscious and explicit as students’ attention is drawn to linguistic forms and functions for meaning making. Teachers plan lessons based on the content standards and then select and utilize specific language teaching methods and approaches based on identifiable second or world language teaching methodologies (DeKeyser, 2003; Ellis, 2010).

Metalinguistic concepts and contrastive features of both English and Spanish are taught systematically and explicitly. Teachers plan for instruction of specific linguistic forms that may pose difficulty for the L2 learner that become the content focus of the lesson. Effective instruction requires a purposeful selection of second-language teaching methods or approaches that are research-based and have been demonstrated to be effective for supporting and enhancing L2 acquisition and development toward the goal of native-speaker equivalent L2 language proficiency. Language acquisition in a multilingual context is focused on building metalinguistic knowledge, which entails teaching students about how language work. During direct instruction and through structured learning activities, students’ attention is directed to language functions and the particularities English-specific vocabulary, morphology, grammatical or syntactic forms and idiomatic expressions used to think and communicate about the content.

The Language Proficiency Factor

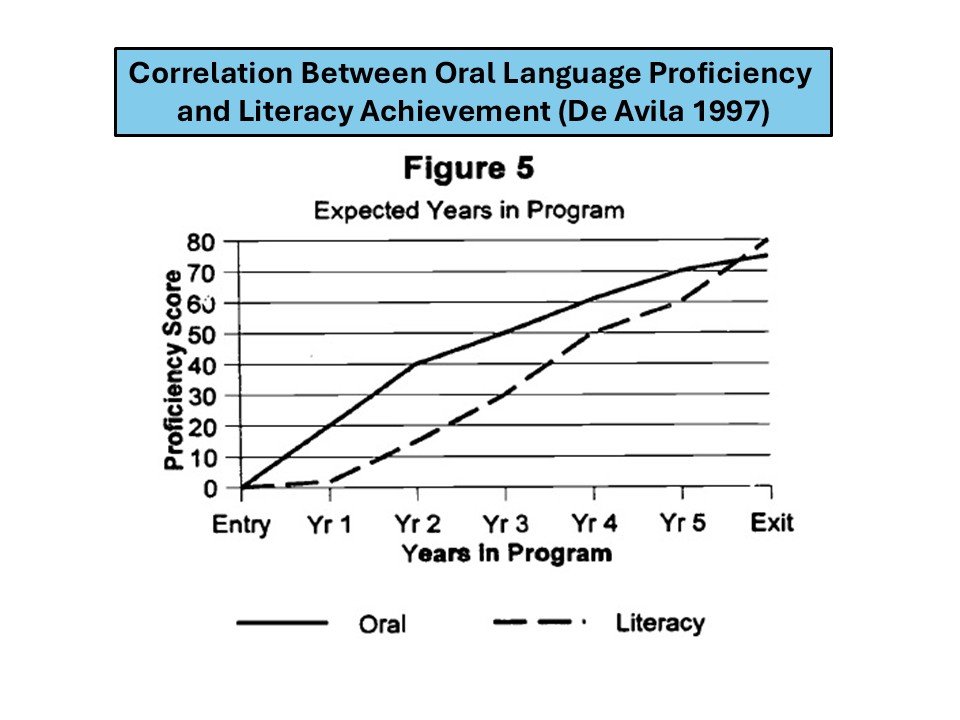

De Avila (1997) studied expected gains in language proficiency based on data from large-scale administration of the Language Assessment Scales proficiency test. Several important observations about language proficiency development over time emerged from this research. Language proficiency consists of both receptive and productive skills, input and output, information sent and received. It is important to observe the different rates of acquisition of both oral and literacy skills according to four domains: listening, speaking, reading and writing. Proficiency in each of the four domains is a necessary element to consider in assessing second-language proficiency, as each contributes to academic success differentially over the process of developing full native-speaker equivalent proficiency. It is noteworthy that the development of literacy skills is somewhat slower at the lower levels of proficiency. Reading and writing skills begin to converge at a level four language proficiency, which usually is achieved after four to five years of exposure and instruction in the L2. However, once minimal oral skills have been established, students move quickly through the middle levels. An implication of these findings is an expected gain of one proficiency level per academic year with equivalent achievement in reading and writing is misleading.

De Avila (1997) studied expected gains in language proficiency based on data from large-scale administration of the Language Assessment Scales proficiency test. Several important observations about language proficiency development over time emerged from this research. Language proficiency consists of both receptive and productive skills, input and output, information sent and received. It is important to observe the different rates of acquisition of both oral and literacy skills according to four domains: listening, speaking, reading and writing. Proficiency in each of the four domains is a necessary element to consider in assessing second-language proficiency, as each contributes to academic success differentially over the process of developing full native-speaker equivalent proficiency. It is noteworthy that the development of literacy skills is somewhat slower at the lower levels of proficiency. Reading and writing skills begin to converge at a level four language proficiency, which usually is achieved after four to five years of exposure and instruction in the L2. However, once minimal oral skills have been established, students move quickly through the middle levels. An implication of these findings is an expected gain of one proficiency level per academic year with equivalent achievement in reading and writing is misleading.

According to research on expected gains in English language proficiency over time (De Avila, 1997), ELs may not reasonably be expected to demonstrate on-grade-level performance on reading achievement tests until fourth or fifth grade or beyond. On the other hand, growth in oral proficiency is rapid, particularly in listening skills. Consequently, the acquisition of English as a second language develops in a non-linear fashion. According to these data, initial programmatic emphasis, at least at the elementary level, should be directed toward the development of beginning oral skills with modified and scaffolded instruction in reading and writing.

Second Language Reading Research

First language reading research is restricted to monolingual processing of written text that meld and interface, while L2 reading research considers learners’ first and second-language processing experiences and their probable interplay as well as the two languages’ influence on each other. Consequently, L2 reading research and pedagogy draw heavily from linguistics and psycholinguistics research paradigms (Traxler, 2023).

The knowledge base for literacy instruction for multilingual learners is further reinforced by investigations of L2 reading (Bernhardt, 1998; Bernhardt & Kamil, 1995; Koda, 2004). Second language reading is recognized as a phenomenon unto itself, with distinct characteristics and trajectories attributable to the interaction between language proficiency and literacy learning. Three prerequisite skills for the acquisition of literacy are competence with the oral language, understanding of symbolic concepts of print, and establishment of metalinguistic awareness (Bialystok, 2007).This field of inquiry is based on a multifactor theory that presupposes an interactive, multidimensional dynamic of literacy elements’ development along a continuum of L2 proficiency.

The underlying assumption is that second language learners must acquire a certain level of oral proficiency in their new language to benefit fully from instruction in reading and writing. This is because the phonology, vocabulary and grammar of their L2 is different from their native language. L2 reading research explores variables in text comprehension such as word recognition, vocabulary knowledge, syntax, phonology, and text structure through the perspective of language competencies as an integrative process (Jeon & Yamashita, 2014). Bernhardt attributes different error patterns (miscues) during oral reading performance in developing L2 literacy to readers’ risk-taking and to the increased potential for misusing and misunderstanding complex syntactic forms, which tend to decline as language proficiency increases. Second language reading research and metalinguistics also examine the contribution of other factors of language and literacy learning such as processes for inferencing the meaning of words, phrases and sentences that L2 learners employ for both oral comprehension and reading comprehension (Carton, 1971; Haastrup, 2009).

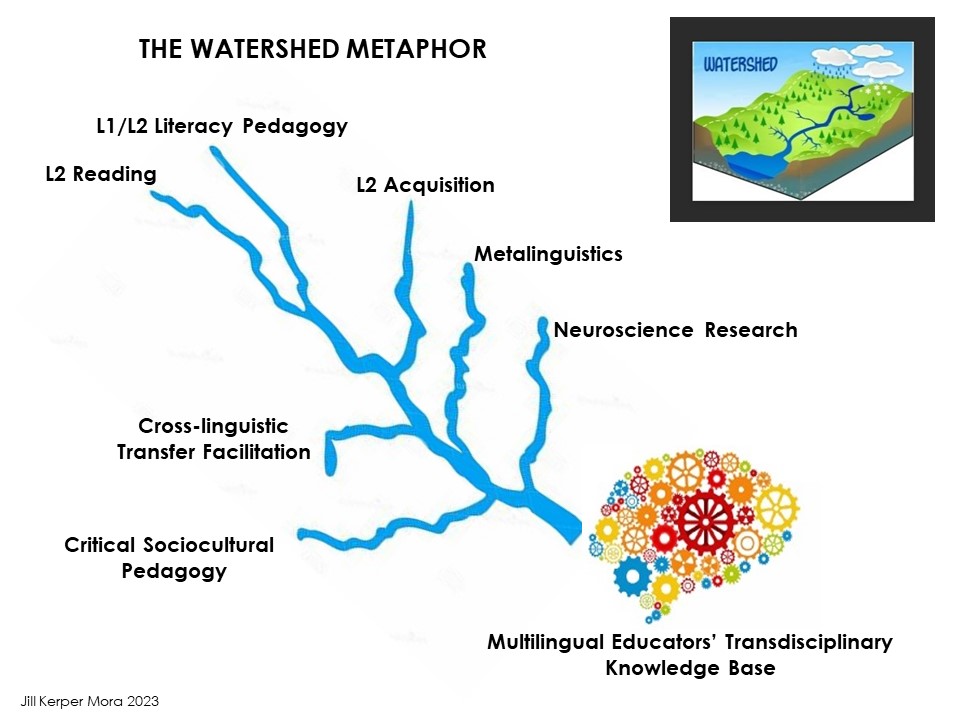

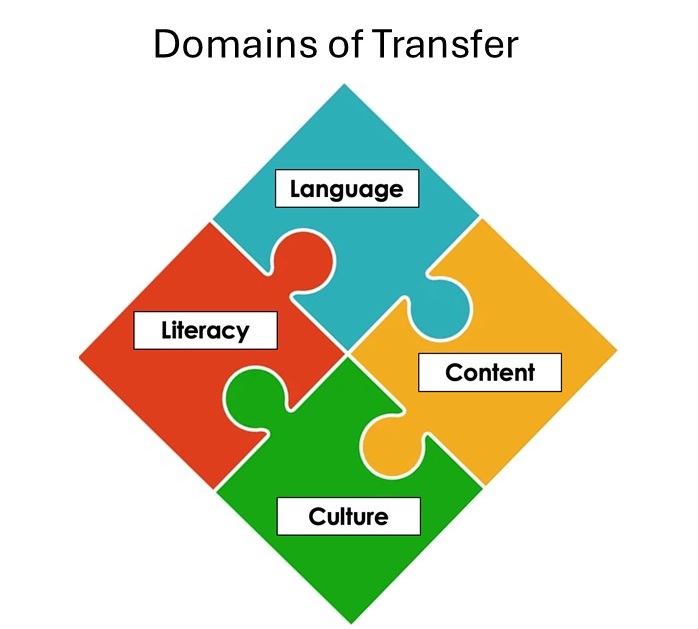

Metalinguistics

The field of metalinguistics examines interlingual relationships to discern the shared and unique contributions of awareness of the operations of defined subsystems of language in reading development and performance. Ke, et al. (2023) conducted a meta-analysis of empirical studies that identify multiple direct and indirect paths that connect metalinguistic awareness, reading comprehension and vocabulary knowledge together as reading-related outcomes. These studies explain both shared metalinguistic awareness and language-specific metalinguistic awareness as empirical evidence of the extent of cross-linguistic transfer in literacy development. Koda’s Transfer Facilitation Model provides predictions on multiple factors that affect transfer of subskills in L2 reading and identifies conditions that promote cross-linguistic transfer. The operational hypothesis is that the language proficiency underlying cognitively demanding tasks, such as literacy and academic learning, is largely shared across languages, and therefore, linguistic competencies acquired in one language promote literacy development in another (Cummins, 2021; Gombert, 1992: Tunmer & Bowey, 1984; Yaden & Templeton, 1986).

The theoretical construct of metalinguistic awareness, knowledge and control describes the ability to make language forms objective and explicit and to attend to them in and for themselves. Metalinguistic awareness is the ability to view and analyze language as a “thing,” language as a “process,” and language as a “system” (Ke, et al., 2023). Metalinguistic knowledge development requires attention to the components of language beyond the language learner’s implicit and practical knowledge and use of language for practical purposes. Koda (2008) proposed a transfer facilitation model based on the research findings that reading skills transfer across languages. The specific metalinguistic competencies involved in fluent and proficient biliteracy that transfer across languages and writing systems can be identified according to the embedded and/or explicit knowledge of how spoken and written language are related through an alphabetic spelling system.

Metalinguistic transfer is the application of particular metalinguistic awareness and knowledge acquired in students’ L1 to listening, speaking, reading and writing in their L2 English. In bilingual learners, students form sensitivity to the regularities of spoken language as they develop oral language skills. Since all writing systems are structured to capture and represent these regularities, learning to read involves mapping spoken language elements onto the graphic symbols of the language of the text (Varga, 2021). Multilingual awareness enables learners to analyze spoken words into their constituent parts. This process becomes more explicit with increasing experiences with print. As first-language metalinguistic awareness is established, bilingual readers can automatically activate and apply this skill to reading in their second language. Development of metalinguistic knowledge also entails the ability to compare and contrast two language systems to discover commonalities as well as differences. Apel (2022) concludes that evidence from different lines of research demonstrates the important contributions of multiple metalinguistic skills (e.g., phonological awareness, morphological awareness, syntactic awareness) to reading comprehension, and therefore, instruction that includes a focus on these multiple language awareness skills is recommended for literacy instruction for all learners, but especially for multilingual learners such as EL/EB classified students (Cheung & Slavin, 2012).

Koda (2008) defines transfer as “… an automatic activation of well-established first-language competencies, triggered by second-language input.” For transfer to occur, the competencies to be transferred must be well established, to the point of automaticity in the reader’s L1. Koda (2008:77) proposed a Transfer Facilitation Model that outlines several fundamental premises of skills transfer in biliteracy learning. Children form sensitivity to the regularities of spoken language as they develop oral language skills at an age-peer appropriate level upon entering school in their native language. Learning to read involves mapping spoken language elements onto written symbols of the language of the text. Metalinguistic awareness enables learners to analyze spoken words into their constituent parts so that they can decode written text. This process becomes more explicit through cumulative experiences with print. The result of metalinguistic abilities acquired in L1 and L2 is increased awareness of the specific ways in which regularities of language are represented in the writing system and how written language varies systematically in the two languages that the students are learning to read. The metalinguistic model of teaching for transfer depicts the overlap and distinctions necessary for understanding cross-linguistic transfer of reading skills.

Lexical Inferencing

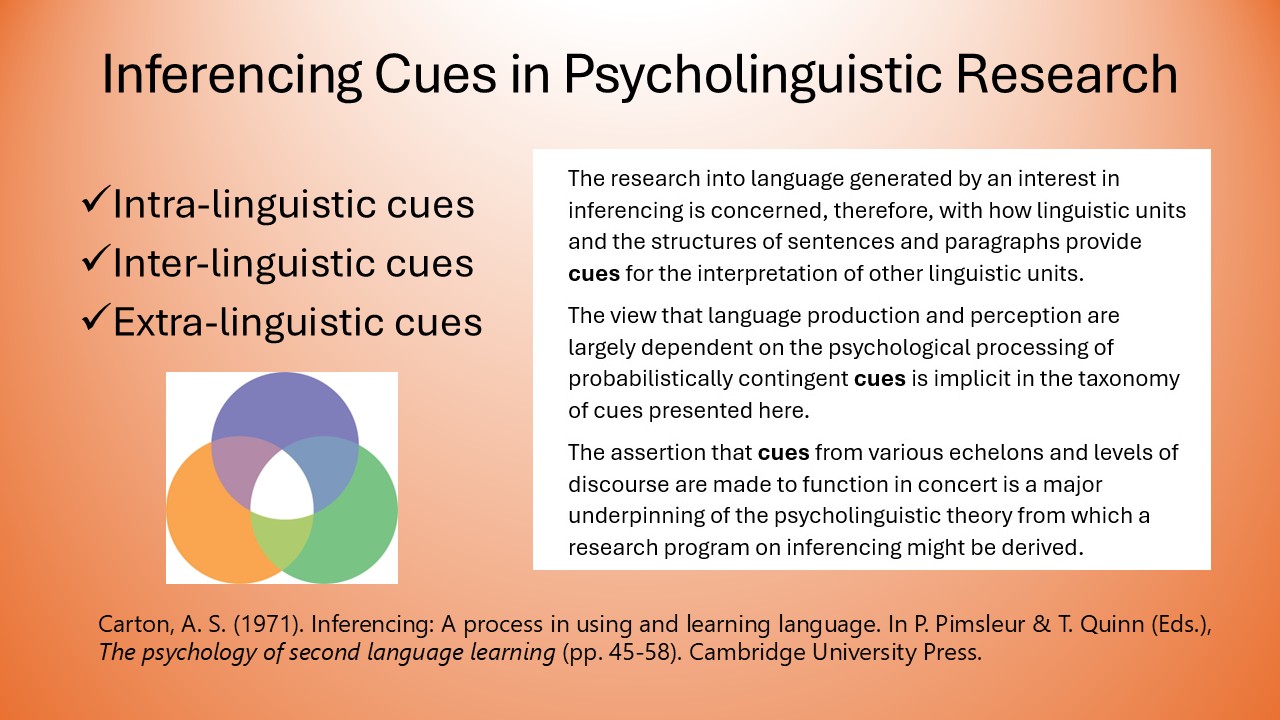

Inferencing is a sub-type of the more general inferencing process that operates at all levels of text comprehension, involving the connections people make when attempting to reach an interpretation of what they read or hear. Lexical inferencing is seen as operating at the core of the relationship between reading comprehension and vocabulary development (Carton, 1971; Chun, 2020). Haarstrup (2009) conducted a meta-analysis of research relevant to the issue of L1 transfer in L2 lexical inferencing and to cross-linguistic commonalities and L1/L2 differences in lexical inferencing. Carton (1971) describes the interest in inferencing in second language learning this way:

Inferencing is a sub-type of the more general inferencing process that operates at all levels of text comprehension, involving the connections people make when attempting to reach an interpretation of what they read or hear. Lexical inferencing is seen as operating at the core of the relationship between reading comprehension and vocabulary development (Carton, 1971; Chun, 2020). Haarstrup (2009) conducted a meta-analysis of research relevant to the issue of L1 transfer in L2 lexical inferencing and to cross-linguistic commonalities and L1/L2 differences in lexical inferencing. Carton (1971) describes the interest in inferencing in second language learning this way:

It is argued here that it is precisely the perception of probabilistically contingent relations (both in language and in respect to the’ content’ of messages) that enhances and provides possibilities for the selection of appropriate linguistic units in production and the correct interpretation of these units in comprehension. The research into language generated by an interest in inferencing is concerned, therefore, with how linguistic units and the structures of sentences and paragraphs provide cues for the interpretation of other linguistic units. The view that language production and perception are largely dependent on the psychological processing of probabilistically contingent cues is implicit in the taxonomy of cues presented here. The assertion that cues from various echelons and levels of discourse are made to function in concert is a major underpinning of the psycholinguistic theory from which a research program on inferencing might be derived. (p. 57)

A language pedagogy that utilizes inferencing removes language study from the domain of mere skills to a domain that is more closely akin to the regions of complex intellectual processes. Language study becomes a matter for a kind of problem-solving and the entire breadth of the student’s experience and knowledge may be brought to bear on the processing of language.( p. 57-58) Haarstrup (2009) conducted a meta-analysis of research relevant to the issue of L1 transfer in L2 lexical inferencing and to cross-linguistic commonalities and L1/L2 differences in lexical inferencing. Inferencing is a sub-type of the more general inferencing process that operates at all levels of text comprehension, involving the connections people make when attempting to reach an interpretation of what they read or hear. Lexical inferencing is seen as operating at the core of the relationship between reading comprehension and vocabulary development.

Implications for Multilingual Learners’ Literacy Instruction

The most important implication of Claim 3 regarding the linkage between oral language comprehension of words, sentences and discourse that EL/EB students encounter in learning to read and write in English as a second language centers around the broad issue of language proficiency. Language proficiency must be viewed from the perspective of the different rates of growth in listening, speaking, reading and writing. Instructional decision-making for EL/EB learners is based on a clear understanding of how students’ L2 proficiency levels impact literacy acquisition in their L2 (Birch, 2007; Lems, et al., 2010). An assets-based approach to literacy instruction is based on a pedagogical orientation that affirms the language-specific knowledge of how language works as the foundation for metalinguistic awareness that supports and enhances literacy and biliteracy learning (Mora & Dorta-Duque de Reyes, 2025; Zoeller & Briceño, 2022). A metalinguistic transfer facilitation approach to literacy instruction is highly recommended. Teachers of multilingual learners must keep in mind that learning how language works involves making implicit knowledge about the student’s first or native language explicit in order to utilize this knowledge to learn to speak, read and write in their L2. Ellis (2010) describes the process this way: Even though implicitly acquired knowledge tends to remain implicit, and explicitly acquired knowledge tends to remain explicit, explicitly learned knowledge can become implicit in the sense that learners can lose awareness of its structure over time, and learners can become aware of the structure of implicit knowledge when attempting to access it, for example for applying it to a new context or for conveying it verbally to somebody else. (p. 315). Honoring the assets that multilingual learners bring to their literacy learning context. Standards-based literacy instruction that is based on contrastive analysis and metalinguistic knowledge development is the pathway to academic achievement for multilingual learners. See the Linguistic Augmentation for the Spanish Common Core en Español standards (Destrezas).

REFERENCES Claim 3

Bernhardt, E. B. (1998). Reading development in a second language: Theoretical, empirical and classroom perspectives. Ablex.

Bernhardt, E. B., & Kamil, M. L. (1995). Interpreting relationships between L1 and L2 reading: Consolidating the Linguistic Threshold and the Linguistic Interdependence hypotheses. Applied Linguistics, 16(1), 15-34.

Bialystok, E. (2007). Acquisition of literacy in bilingual children: A framework for research. Language Learning, 57(Supp), 45-77.

Birch, B. M. (2007). English L2 reading: Getting to the bottom (Second ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Carton, A. S. (1971). Inferencing: A process in using and learning language. In P. Pimsleur & T. Quinn (Eds.), The psychology of second language learning (pp. 45-58). Cambridge University Press.

Cheung, A. C. K., & Slavin, R. E. (2012). Effective reading programs for Spanish-dominant English Language Learners (ELLs) in the elementary grades: A synthesis of Research. American Education Research Journal, 82(4), 351-395.

Chun, E. (2020). L2 prediction guided by linguistic experience. English Teaching, 75, 79-103.

Cummins, J. (2021). Rethinking the education of multilingual learners: A critical analysis of theoretical concepts. Multilingual Matters.

DeKeyser, R. (2003). Implicit and explicit learning. In C. J. Doughty & M. H. Long (Eds.), The handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 313-348). John Wiley & Sons.

Ellis, R. (2010). Second language acquisition, teacher education and language pedagogy. Language Teaching, 43(2), 182-201.

Gombert, J. E. (1992). Metalinguistic Development. Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1993). Towards a language-based theory of learning. Linguistics and Education, 5(2), 93-116.

Haastrup, K. (2009). Research on the lexical inferencing process and its outcomes. In M. B. Wesche & T. S. Paribakht (Eds.), Lexical inferencing in a first and second language: Cross-linguistic dimensions (pp. 3-30). Multilingual Matters.

Jeon, E. H., & Yamashita, J. (2014). L2 reading comprehension and its correlates: A meta-analysis. Language Learning, 64(1), 160-212.

Ke, S. E., Zhang, D., & Koda, K. (2023). Metalinguistic awareness in second language reading development. Cambridge University Press.

Koda, K. (2004). Insights into second language reading: A cross-linguistic approach. Cambridge University Press.

Koda, K. (2008). Impacts of prior literacy experience on second language learning to read. In K. Koda & A. M. Zehler (Eds.), Learning to Read Across Languages (pp. 68-96). Routledge.

Lems, K., Miller, L. D., & Soro, T. M. (2010). Teaching reading to English language learners: Insights from linguistics. The Guilford Press.

Mora, J. K. (2025). Spanish language pedagogy for biliteracy programs (Second ed.). Montezuma Publishing.

Mora, J. K. (2024a). Reaffirming multilingual educators’ pedagogical knowledge base. Multilingual Educator, February(CABE 2024 Edition), 12-14.

Mora, J. K. (2024b). “Where do I start?” An overview of the pedagogical knowledge base for implementing English Language Development standards. The California Reader, 57(3), 13-20.

Mora, J. K., & Dorta-Duque de Reyes, S. (In press). Biliteracy and cross-cultural teaching: A framework for standards-based transfer instruction in dual language programs. Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

Tunmer, W.E., & Bowey, J.A. (1984). Metalinguistic awareness and reading acquisition. In W.E. Tunmer, C. Pratt, & M.L. Herriman (Eds.), Metalinguistic awareness in children (pp. 144–168). New York: Springer-Verlag.

Traxler, M. J. (2023). Introduction to psycholinguistics (Second ed.). Wiley Blackwell.

Valdés, G., Menken, K., & Castro, M. (Eds.). (2015). Common Core bilingual and English language learners: A source for educators. Caslon Publishing.

Varga, S. (2021). The relationship between reading skills and metalinguistic awareness. Gradus, 8(1), 52-57.

Yaden, D. B., & Templeton, S. (Eds.). (1986). Metalinguistic awareness and beginning literacy: Conceptualizing what it means to read and write. Heinemann.

Zoeller, E., & Briceño, A. (2022). An asset-based practice for teaching bilingual readers. The Reading Teacher, 76(1), 92-96.

SoR CLAIM 4

Phonics facilitates the increasingly automatic identification of unfamiliar words.

Tierney, R. J., & Pearson, P. D. (2024). Fact-checking the Science of Reading: Opening up the conversation. Literacy Research Commons.

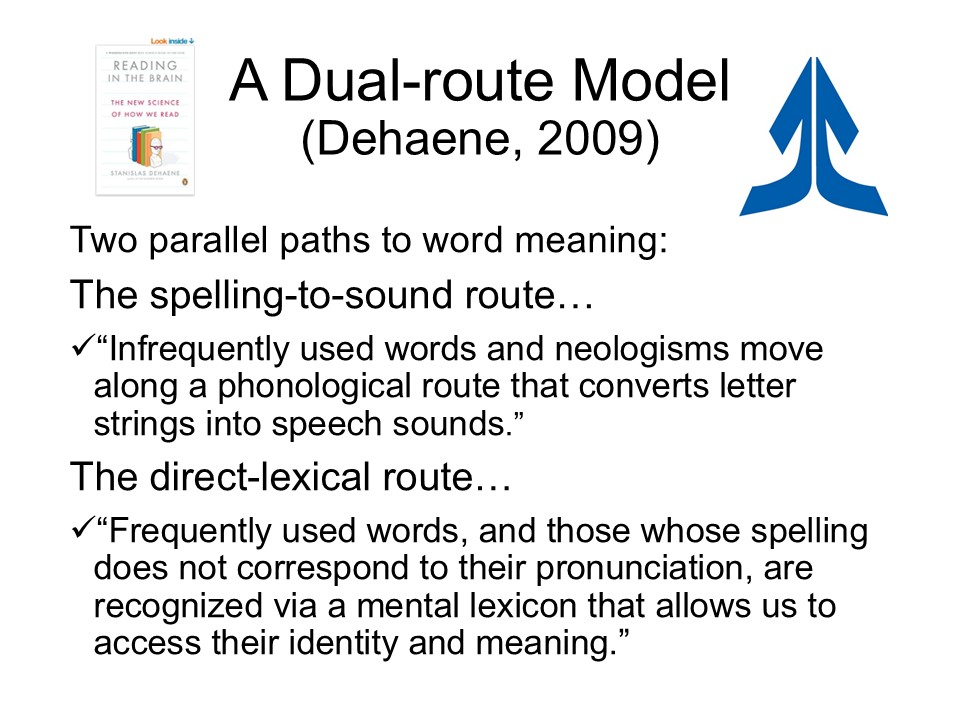

Claim 4 is based on a interpretation of research on decoding skills, orthographic mapping and word recognition or identification skills. The manner in which words are processed to establish their spelling and meaning in memory automatically is the major concern of the research on decoding skills in the acquisition of fluent reading in emergent readers. One of these research questions involves the role of “contextual information, such as semantics, syntax and pragmatics in word recognition (Ehri, 2021). The concept of “unfamiliar words” versus words that are easily decodable or are learned as sight words entails differing perspectives on the role of “guessing” in establishing automaticity in word recognition processes.

Tierney and Pearson (2024: 53) state the following: “We are not aware of any evidence that suggests that context cannot aid the development of orthographic mapping.” (p. 53) These authors also state that they have “mixed views on the acceptability” of Claim 4, depending on the researchers’ focus on word-by-word reading accuracy versus a range of word-solving strategies that facilitate automatic identification of unfamiliar words. These authors assert that both perspectives rest on the presumption that naming words is key to learning to read (p, 54). Consequently, the issue for second-language readers of English is the role of orthographic mapping in learning to read in their native language (L1) and orthographic mapping in their not-yet-native-proficiency English as a second language (L2).